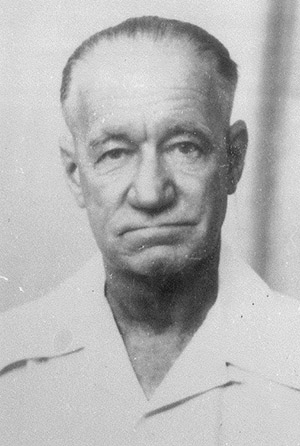

ACKLAND, ARTHUR BELL (HOP) ED MBE OBE

ACKLAND, ARTHUR BELL (HOP) ED MBE OBE

(September 06, 1894 — July 22, 1971)

Fiji Constabulary 1915

World War I 1916-1919

Colonial Secretary’s Office 1919

Lieutenant, Fiji Defence Force, 1920

Dept of Agriculture 1920-1938

Produce Inspector 1931-1941

Commanded 1st Battalion, Fiji Labour Corps, 1942-45

Native Land Trust Board 1945

Started Fiji Banana Ventures 1950-1959

Left Fiji for Auckland, NZ 1959.

By Jim Ackland from the book The Acklands of Fiji by Betty Hunt (nee Ackland).

![]()

Arthur (Hop) Ackland’s parents were Charles Bell Ackland and Grace Walcot. As children they attended the same school in Timaru, NZ, later both meeting again when their parents moved to Sydney in the 1880s. In 1892 they married.

Their first born was Philip (Lip) in 1893, then Dad, Arthur (Hop) in 1894. The family moved to Ba, in Fiji in 1895 where they completed their family with Nea (Nin) born in 1896, later married Walter (Steve) Stevenson, Ralph (Spec) in 1898 who married Cecilia (Suzie) St Julian and Adele (Sally) in 1900 who married Arthur (Don) Donald.

Dad attended the Suva Public School when the family moved to Suva in 1902 and in 1909, he left school to take up employment with a Suva shipping firm. In 1913 he joined the Government service as a 5th class clerk in the Constabulary and was soon transferred to the Colonial Secretary’s office. He served four years with the local Defence Cadets, a territorial Army Unit, and played in and later referreed their rugby team.

Came World War 1. His Department was unwilling to release him but he finally got his way. He had already been an active participant in defence preparations against a possible German navy raid on Cable and Wireless installations. Twenty names were published in the Gazette as citizens “who rendered excellent service in connection with the defence of Fiji at the outbreak of war”. including Sgt A.B.Ackland. The local newspaper dubbed them “The Gallant Twenty”.

Most volunteers from Fiji went in contingents to the Royal Greenjackets, while others joined Australian and NZ armies. Dad went to the 17th Battalion of the AIF – 5′ 6” tall, weight 9 stone and chest 34”. He enlisted in Sydney in 1915, embarked for Europe in March 1916 and joined his unit in France in September. Dad survived the war unwounded but succumbed late in 1920 to post traumatic stress and was granted four months overseas leave.

Between the wars

On Dad’s return he was transferred to the Dept of Agriculture. He quickly earned a reputation for efficiency and in 1926 was promoted to 1st Class Clerk. Government administration was carried out by clerks, as distinct from specialists such as surveyors, engineers &c. These days such posts have fancy names.

Early in 1920 Dad was appointed acting Sub Inspector of Constabulary. One of his first tasks though, was to manage a dairy scheme established in Tailevu to support returned soldiers. He also played a role in attempts to create a rice industry and to revive the cotton industry. When the Levuana Moth threatened the copra industry he gave support to Entomologist H.W.Simmonds who introduced a predator.

He acquired a wide and detailed knowledge of agricultural matters, especially marketing, which led to his attendance as Fiji’s representative at international exhibitions and special missions. In the 1930s he acted as Director and as such a member of Legislative Council.

Dad was involved with a number of activities outside his employment. His main enthusiasm was for the Territorial Army. He was commissioned as a Lieutenant in 1920 and awarded the Efficiency Decoration. He befriended a number of young officers, scallywags at the time, who went on to high office. They formed a deep and abiding respect for him. They included Ratu Sir George Cakobau and Ratu Sir Edward Cakobau. Both these chiefs saw active service on Bougainville. Also Sir Maurice Scott, legendary playboy and brilliant spokesman for Fijian interests. His other passion was Fijian rugby. Dad was charged by the Rugby Union to set up and control a Fijian competition – played in bare feet.

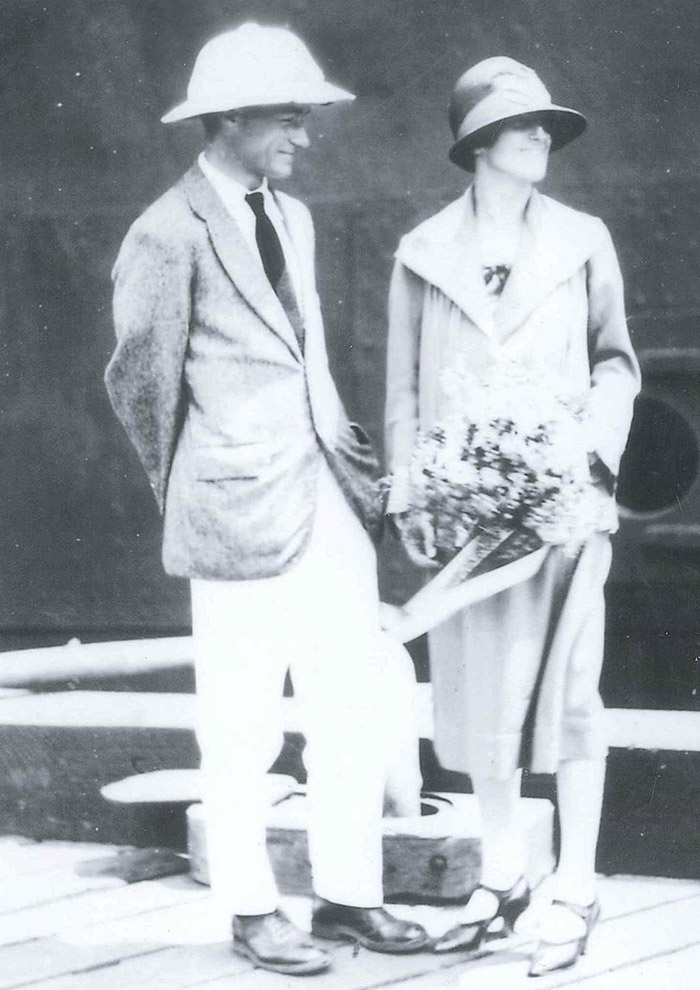

I believe he must have been a man about town in the early 20’s. Apparently he had some rather wild companions. He had a boat called Willy Go. Then he met Mum – Jessie Dick.

Jessie was a member of a large Auckland family whose parents were devout members of the Church of Christ and did not tolerate drinking and other simple pleasures. After a broken engagement, her parents decided she needed a change of scene and arranged employment at AM Brodziak in Suva.

And so it was an innocent abroad who arrived in December 1923 and took up residence at the Oceanic Guesthouse. Her fellow boarders promptly adapted her name to Dickie. She kept a diary, describing the high life of a spirited young woman recently freed from parental restraints.

Very soon after she met Dad and they married on 8 Oct 1926. He was 32 and Jessie 24. She presented Dad with four children, Jim in 1928, Jean in 1932 and twins Bill and Betty in 1938.

Early years they lived in a spacious house in Waimanu Road, and in the late 1930s the family moved to Suva Point. Dad then organised working bees to establish the tennis courts opposite our home for the local community. Mum never took up employment as was the custom in those days but devoted her time to her family and to her many friends.

The Great Depression of the early 1930s affected Fiji as much as any other country and civil servants and private sector employees had to accept a cut in salary. Dad was member/chairman of a board set up to organize relief measures, member/deputy chairman of the Suva Town Board, and secretary of the Defence Club in its early years – a club whose members undertook to offer their services to Govt in an emergency.

Suva was a pleasant place to live in spite of the depression years. The Fijians were content. Pax Britannica had relieved them of the need to be constantly on guard against attacks by neighbouring tribes. They lived in a state of what might be termed “affluent subsistence” in their well ordered villages. The Colonial Government provided medical services and schools. Methodist missionaries converted fierce warriors into fervent churchgoers.

Fijians were fascinated to find that Europeans shared with them similar standards of toleration and courtesy. For their part the Europeans enjoyed their company and their sense of humour. It never entered Fijian heads that they would be considered anything other than being equal but different. This relationship was exemplified in the army where Fijians and Europeans served together in every rank and with great harmony.

The Indian community was less content. They were brought to Fiji as indentured labour 1879 to 1919 and contributed much to the prosperity of Fiji in the cane fields and commerce. While most of them exercised their option to remain in Fiji on expiry of their indenture, they nevertheless were not satisfied with their status.

Soon after WW I and inspired by the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi they commenced a campaign through their representatives in Legislative Council for a Common Roll, that is, ideal democracy with one man one vote regardless of race. The Colonial Office view that Fiji was not quite ready for this step led to the Indian Community’s boycott of the WW II war effort.

The Europeans were a closed society in the days before tourism. A new resident would have his name published in the local paper as having arrived on such and such a vessel, promoting speculation as to what clubs he might be admitted to. People led an active social life which depended on Fijian and Indian servants.

Fijian women would offer themselves for employment. Quarters and food would be provided and not much pay. For their part they didn’t understand a master/servant relationship and considered themselves part of the family. Man and wife could attend social functions knowing that their children would receive affectionate attention at home. Indian servants were hired mainly for their cooking expertise.

Shopping was conducted by phone and lorries would deliver groceries, meat and fish, ice for the ice chest, fruit and veg, bread and milk etc. Clothes were made to measure by Indian tailors and shoes hand made. Both Government and the private sector adopted a 1½ hour lunch time so people went home for the main meal of the day. Saturday was a work day to 12 noon.

Men wore a starched white jacket to work and to the pictures. Swimming destinations were Suva Point and at the Cascades at Tamavua. Boating destinations were to Mosquito Island and Nukulau where huts originally built to quarantine Indian indentured labour provided spacious camping facilities.

2nd World War

The Hun was on the warpath in 1939. Dad was commander of the Fijian Company of the Defence Force. I recall watching an exercise where sailors from a British warship conducted a landing in ship’s boats at Suva Point with the aim of capturing the nearby Cable and Wireless station, stoutly defended by the Defence Force. About 1940 the family moved to Auckland while Dad attended military training at Narrow Neck Camp.

Energetic steps were taken to put Fiji on a war footing. Practically every male European volunteered to serve in the Regular Army, the Territorial Army or the Home Guard. Defended areas were established at Suva and Lautoka and an airfield constructed at Nadi. 6” and 4” guns were emplaced, barbed wire on the beaches ringed the Suva peninsula and searchlights swept the sea. A seaplane base was established at Suva Point behind a breakwater. Two ancient Short Singapore flying boats carried out surveillance.

The attack on Pearl Harbour added impetus to the preparations. The Japanese wanted Fiji as one of their strongholds to guard their newly acquired South East Asian empire. The Americans also needed a base in Fiji for their operations in the South West Pacific. Suddenly, Suva became a major port as supplies flowed in.

The Defence Force, renamed the Fiji Military Force, was expanded to five battalions, two of which engaged with the Japanese in the Solomons earning commendations from US commanders. Commando units, field artillery in addition to coastal artillery plus the usual service units, were formed. A brigade group was prepared for overseas deployment. A number of young men served in the Royal Air Force with distinction.

The Defence Force, renamed the Fiji Military Force, was expanded to five battalions, two of which engaged with the Japanese in the Solomons earning commendations from US commanders. Commando units, field artillery in addition to coastal artillery plus the usual service units, were formed. A brigade group was prepared for overseas deployment. A number of young men served in the Royal Air Force with distinction.

Dad, despite his vigorous protests, was adjudged too old at 48 for combat. He was then 2IC of the Territorial Battalion. However a task awaited him. The Suva wharves were geared to handle half a dozen ships a month and were inundated with the inflow of ships bringing hundreds of thousands of tons of cargo weekly.

The Fiji Military Forces decided to form a Labour Battalion to handle the problem and Dad in the rank of Lieut Colonel was to command it. He had to do it in a hurry and from scratch. He had to find 1,400 all ranks, none of whom had military training and form them into a disciplined effective unit. The battalion worked three shifts round the clock.

Dad needed all his man management skills to handle the autocratic Fijian chiefs who were his officers and the rank and file Fijians not known for their toleration of sustained hard labour. In fact the battalion entered on its task with great enthusiasm to the delight of US Army commanders who were mightily impressed with the efficiency of the operation in contrast with ports in Australia and New Zealand.

He was also chairman of the Fiji Servicemen’s Welfare Fund set up to provide amenities for the troops.

Post war

Between the wars Ratu Sukuna had been engaged in ascertaining boundaries of land owned by the various tribal sub groups. This was an essential precondition before land could be leased and it needed a body to administer the land on behalf of the Fijians.

It was decided to set up the Native Land Trust Board, and Dad was appointed to head it. He and two Fijian officers were sent to the UK for training in 1945 where they attended courses at Aberystwyth and Cambridge Universities.

In 1948 Dad built his first home in Statham Street, Suva Point. Owen Chapman drew up plans of a four bedroom home, double block exterior walls with wide verandahs on two sides. Dad was clerk of works, hiring labour to do the building work.

The verandah was the scene of Sunday midday gatherings where friends and neighbours would bring their own home brew and enjoy a social hour or two. It was during one of these occasions that local resident, the Rev Dr George Hemming, stopped and joined the party.

He pointed out that he had been engaged in worship while we were all drinking beer. He was well received and the upshot was that the assembly all supported the Rev Dr in his plan to build a church at Suva Point. They formed the nucleus of a working bee that laboured every Sunday morning in its construction, a charming little church built of stone. After the working bee the participants would gather on the Ackland verandah….

(Left – Joan Chalmers. Right – Dad, Bert Agnew, ? ? Cecil Chapman, ? Bill Bygrave, Keith Black, Tommy Mayfield?)

Dad was for many years President of the Fiji Returned Services Association and in 1950 was awarded the MBE for his services to the Colony.

At about this time he left the Native Land Trust Board to establish the Fiji Banana Ventures to market and export bananas to NZ. The logistics of such an operation were daunting as the bananas had to be harvested at the last minute to ensure fresh delivery. The main source of supply was plantations along the Wainimala River. Villagers built bamboo rafts to float the produce down to the packing stations which were set up along the main road. One had to think about cargo space available, demand and supply, having the right number of packing cases at stations, transport and quality control. Supply of crates were the main problem so, with the help of Fijian landowners and Lou Genge, Dad set up a sawmill at Navua. The deal was sealed not by a written contract but by a handshake.

Move to New Zealand

In 1959 Dad, at 65, decided to move to NZ. The first few years were spent in house minding on rural properties. In 1964 they bought a unit at St Heliers in Auckland. His favourite jaunt was his monthly visit to the RSA at Papakura to drink beer with fellow old soldiers. He belonged to the “King’s Empire Veterans” and became president of the local branch. Dad never spoke about his war experiences.

Dad passed away on 22nd July 1971. He had cancer of the throat brought on by a lifetime of heavy smoking. He was buried at Purewa Cemetery with military honours.

Dad retired with few assets after a lifetime of service. He never paraded his achievements or sought celebrity, but gained satisfaction from giving service. His industry, good humour and absolute integrity propelled him into leadership of the many organisations with which he was associated.

He was known for getting things done. He never brought work home. He and my mother did not join in the social whirl and a typical evening for Dad would be a bottle of home brew, a good book and the radio. His way with words was concise and entertaining.

He had remarkable empathy with Fijians who responded with trust and affection to his leadership in a way not extended to others.

His obituary in the Fiji Times referred to his WW II service – “he achieved that control by persuasion, tact and, if that failed, by some steely-eyed straight talking that achieved its purpose but left no rancour because Hop himself was a completely fair man who nursed no grievances. H would probably finish off the severest dressing-down by saying, “Well, now that that’s over, let’s go and have a drink”. It is hard to believe that anybody remembers Hop Ackland with dislike or bitterness. There are thousands who do so with true affection and respect, recalling how good it made them feel just to be in his company. And that is a pretty good epitaph for any man.”

![]()

Entry By: Jim Ackland from the book The Acklands of Fiji by Betty Hunt (nee Ackland), Auckland, New Zealand.