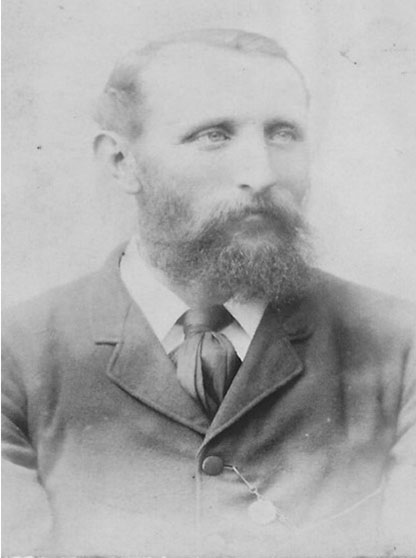

PETRIE, WILLIAM SCOTT

(October 17, 1842 – May 16, 1888)

Cabin boy at age 14 Arbroath, Scotland 1856

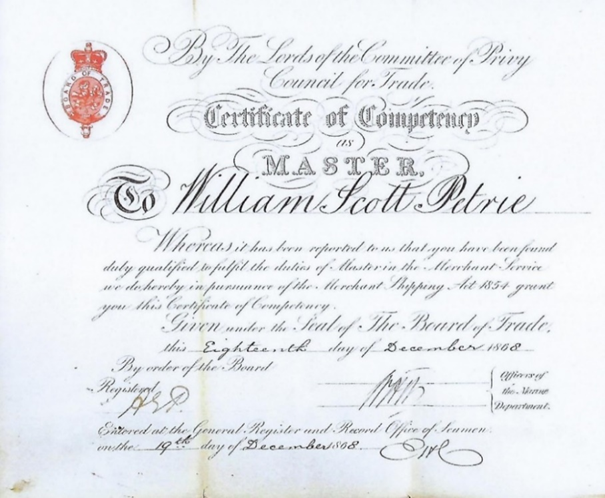

Certificate of Competency as Master, London, England 1868

First Mate ‘Isle of France’, Mauritius 1869 -1870

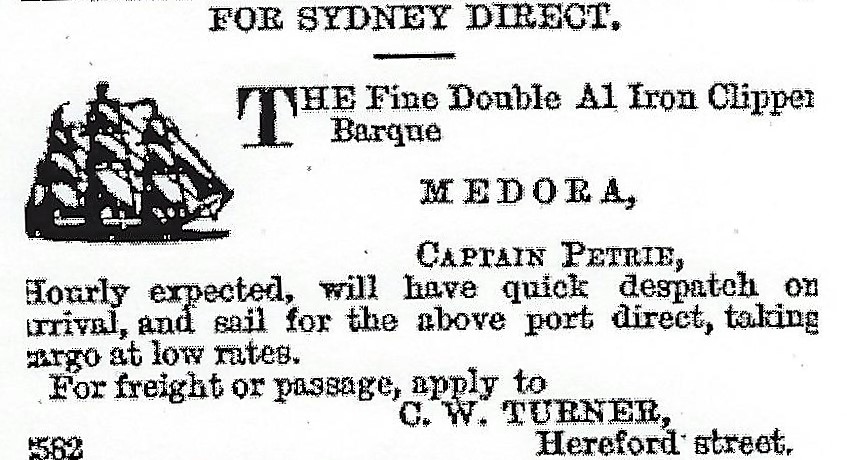

Master of the ‘Medora’, Lyttleton, New Zealand 1873-1876

First Mate various vessels in Australian and Pacific Island waters 1876 – 1879

Master of ‘Windward Ho’, Levuka, Fiji 1880-1884

Perils at sea and at home for a labour recruiter

Moved to Suva, Fiji 1887.

By Michael Abrahams

![]()

Our 2x Great-Grandfather William Scott Petrie was born on 17 October 1842 in Arbroath, Scotland to parents David and Margaret (nee Scott) Petrie, the first of four sons and two daughters. His father was a seaman, as was his maternal Grandfather, William Scott. Therefore, it came as no surprise that young William would choose to go to sea at an early age.

William, of Millgate Loan, Arbroath first turns up on the ‘Neptune’ in 1856 as a cabin boy at the age of 14. His apprenticeship lasts 4 years, served almost entirely on board the ‘Charity’ before attaining the rank of Able-Bodied Seamen on the same Arbroath registered vessel. The next two years were spent on three vessels, ‘Princess Alice,’ the ‘John’ and the ‘Volga’ before he qualified to fulfil the duties of a Second Mate in 1865.

He then served on the Hong Kong registered ‘Zephyr’, followed by the London registered ‘Bengal.’ In May 1867 William qualified as a First Mate, by this time on board the ‘Mary Scott.’ Less than two years later he made application to be examined for a Certificate of Competency as Master. This he attained in December 1868 at the age of 26.

On 28 October 1868, William Scott Petrie married Emma Mary Howard (b. Maidenhead in 1845) at the Parish Church in Wooburn, Buckinghamshire, where Emma was living at the time. Their first child, Maud Wilhelmina Petrie, was born on 3 August 1869 in High Wycombe, just outside London though the birth was not registered until six weeks later.

What happens next is a matter of some conjecture. Clearly the family decides to depart for the other side of the world, though the reasons for doing so are unclear. We do know that a William Petrie applied for a passport in 1860 and may have already travelled abroad, including possibly to the Far East. It appears that at some time in 1869 he picked up a position as the Mate on the Colony of New South Wales registered, Scottish built, 312-ton wooden barque ‘Isle of France’ as he is recorded arriving in Sydney on 14 December of that year from Hong Kong. At a rough guess the family probably travelled as far as Mauritius with him, where he left them and continued to Hong Kong with a load of sugar, returning to Port Louis via Sydney carrying 21,640 lbs of tea, 7,059m bags of rice, 655 rolls of matting and 2,389 packages (of tea?) from Foochow (Fuzhou). William is still Mate on the ‘Isle of France’ when she berths in Sydney on 16 August 1870 from Mauritius with 5,810 bags of sugar. There is no evidence that wife Emma and daughter Maud accompanied him. Could it be that family of crew and non-paying passengers were not always recorded in official documentation? William appears to now pursue work on the Trans-Tasman trade, as well as on coastal shipping in Australian waters, before deciding to head for Lyttleton, New Zealand.

In New Zealand William secures a Master’s position (1873-1876) on the 357-ton iron barque ‘Medora’ which carries a variety of cargoes, including coal from Newcastle, Colony of New South Wales, sugar from Mauritius and tea from China.

In 1874 the ‘Medora’ is reported as having been towed clear of shipping when she spread her canvas in a strong south westerly. She proceeds to Lyttleton with part cargo from Mauritius and transhipments from other vessels. On the return voyage from Foochow in September 1874 the ‘Medora’ gets caught in a typhoon, the third worst in Hong Kong’s history, and loses at least one mast, some spars and rigging. The tea is not seriously damaged and after a refit she proceeds to Dunedin.

On 7 April 1874, a second child, Emma Dora Petrie, is born in Lyttleton.

The following year, on 21 April 1875, the Brig ‘Thomas and Henry’ captained by William and with passengers Mrs Petrie and two children on board sailed for Newcastle, in the Colony of New South Wales. Again, one can only speculate that William left his family in Newcastle or perhaps in Sydney.

William next appears as the Mate on the wooden 72-ton schooner ‘Atlantic’, a known labour recruiting and trading vessel based in Sydney. The ‘Atlantic’ attracted some notoriety when she was stolen by the buccaneer Bully Hayes and used for kidnapping in Fiji waters in 1869. Hayes was arrested in Apia and found guilty, broke parole, and sought refuge in Shanghai before returning some years later to Samoa. He was purportedly murdered by one of his crew in what is know today as the Federated States of Micronesia.

On 26 June 1877, a third daughter, Florence Kate Petrie, was born in Sydney, with her Birth Certificate confirming that Emma and her daughters were residing at 125 Kent Street, Millers Point (as it is known today.) The Sands Sydney and Suburban Directory of 1877 lists Joseph Leddra, Master Mariner, as the principal resident of this property. Kent Street, given its proximity to Sydney’s foreshore and Circular Quay, appears to have been popular with mariners and boat builders. At the time, Leddra was the Master and registered owner of the 255-ton New Brunswick built, and Sydney based, barque the ‘Elm Gove.’ I was equally fascinated to learn that Adolphus Meyer Brodziak, resided at 61 Kent Street. In 1870, he joined his friend Lewis (later Sir Lewis) Cohen in Levuka, where they established Cohen and Brodziak. Three years later this partnership evolved into A M Brodziak and Co. Adolphus returned to Sydney at the end of 1875 after making Simeon Lewis Lazarus Managing Partner of the Fiji company. Lewis Cohen’s sister Leah married my Great-Uncle Abraham Abrahams, also of Levuka.

Petrie’s next move was to the Levuka based 250-ton wooden schooner ‘Dauntless’, again as the First Mate. Between 1877 and 1880 the ’Dauntless’ made five labour recruiting voyages to the New Hebrides and the Solomon Islands and at least once during that time berthed in Sydney (1879), presumably allowing William to catch-up with his family. It is now clear that William’s association with Fiji predates that of the arrival of the family in Levuka.

The 1860’s (labourers from the New Hebrides and the Solomon Islands first arrived in Fiji in 1864) and a large portion of the 1870’s were known by historians as the ‘unregulated’ years of the labour trade and were considered a magnet for less scrupulous operators, some of whom were responsible for shocking atrocities and the use of extremely violent means to recruit plantation workers.

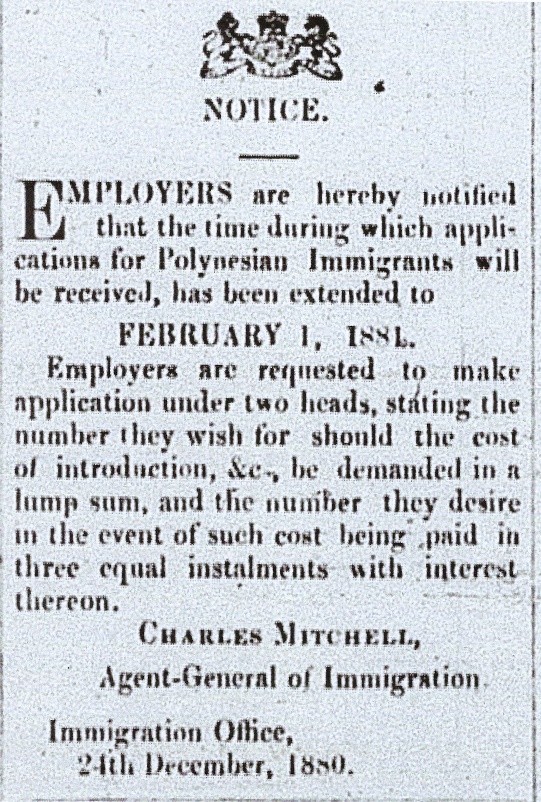

In 1879 the earlier laws (Ordinances XV and X of 1876 and 1877 respectively) governing the recruitment of labourers for Fiji were amended (Ordinance No. XXIV of 5 September) to give greater powers to the Colonial Government to regulate and control this trade. At the end of each year, planters, and others, were required to make application to the Agent General of Immigration for the number of labourers they required for the coming year. When the list of applications was complete, suitable vessels were licenced and chartered by the Government to undertake this task. Each vessel carried a Government Agent on board.

The money for the passage and other expenses were paid, in the first instance, by the Government and repaid by planters in three instalments once the agreed number of labourers had been allotted to them. Each labourer was indentured for three years and not transferable to other holdings, without the permission of the Agent General of Immigration. Wages were set by the Government and the provision of rations mandated. That said, penal sanctions favoured the planters and were widely used as a means of extending contracts or clawing back wages.

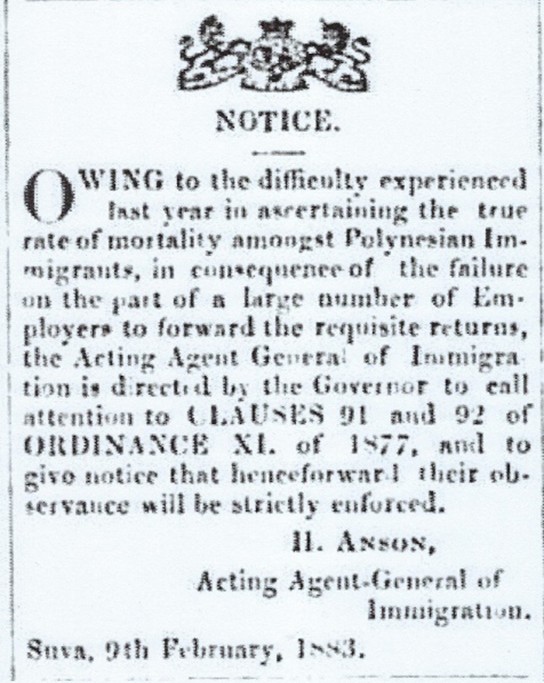

I was interested to note, without exception, that legislation and official documents of the time referred to labourers from the New Hebrides and the Solomon Islands as Polynesian (sic), not only in Fiji but also in Queensland. As best I could determine this broad and inaccurate classification of ethnicity had more to do with administrative convenience and was widely accepted as shorthand for recruits from across the South Pacific. For this reason, I will follow the practice of the time.

Regrettably, the ill-treatment of indentured labour was common, and the provisions of this Ordinance were often honoured in breach. The plantation owners were under an obligation to repatriate these Polynesian (sic) labourers if they wished to return to their island homes to the west of Fiji but not all of them did. Their dependence on this source of labour diminished appreciably from the mid-1880s as, from 1877 onwards, the land owners and the authorities determined that farm labour, to work in the cotton and sugar plantations in Fiji, should be brought from India under strict agreements which included the right to be repatriated. The first shipload of 463 indentured labourers (Girmitiya) from India arrived in Fiji on 15 May 1879 aboard the ‘Leonidas.’

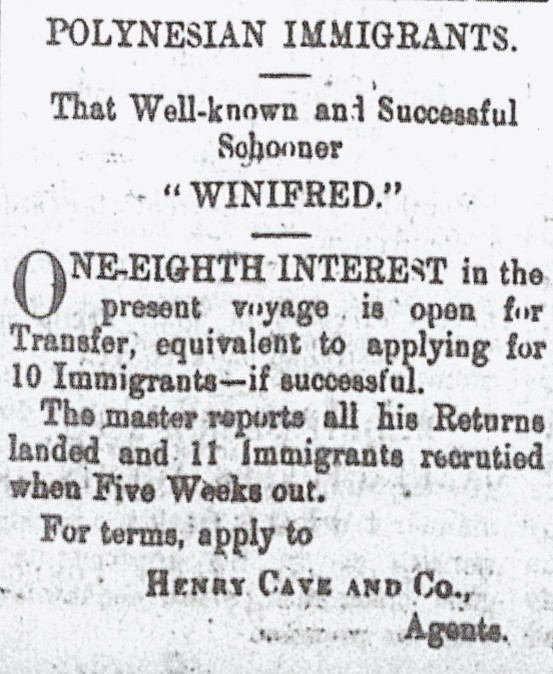

Around this time there were reported to be 18 vessels recruiting labour for Fiji plantation owners in the islands to the Colony’s west. Those registered locally and participating in this trade included the ‘Winifred’ (recorded in the Ships Registry as the ‘Winefred’, though commonly referred to as the ‘Winifred’, as I will do in this article until the error was rectified), ‘Meg Merrilies’, ‘Dauntless’, ‘Ovalau’, and coming alongside them in early 1881 the ‘Windward Ho.’ Rough estimates suggest that these 18 vessels had a combined capacity to deliver annually upwards of 1,400 indentured Melanesian labourers to Fiji. (Estimates vary as to how many Melanesian labourers were brought to Fiji between 1864 and 1911, when recruiting ceased, but it is thought to have been around the 27,000, mostly males. In addition, there were 87 voyages carrying 60,965 indentured Indians to Fiji between 1879 and the arrival of the last ship, the ‘Sutlej’ in November 1916.)

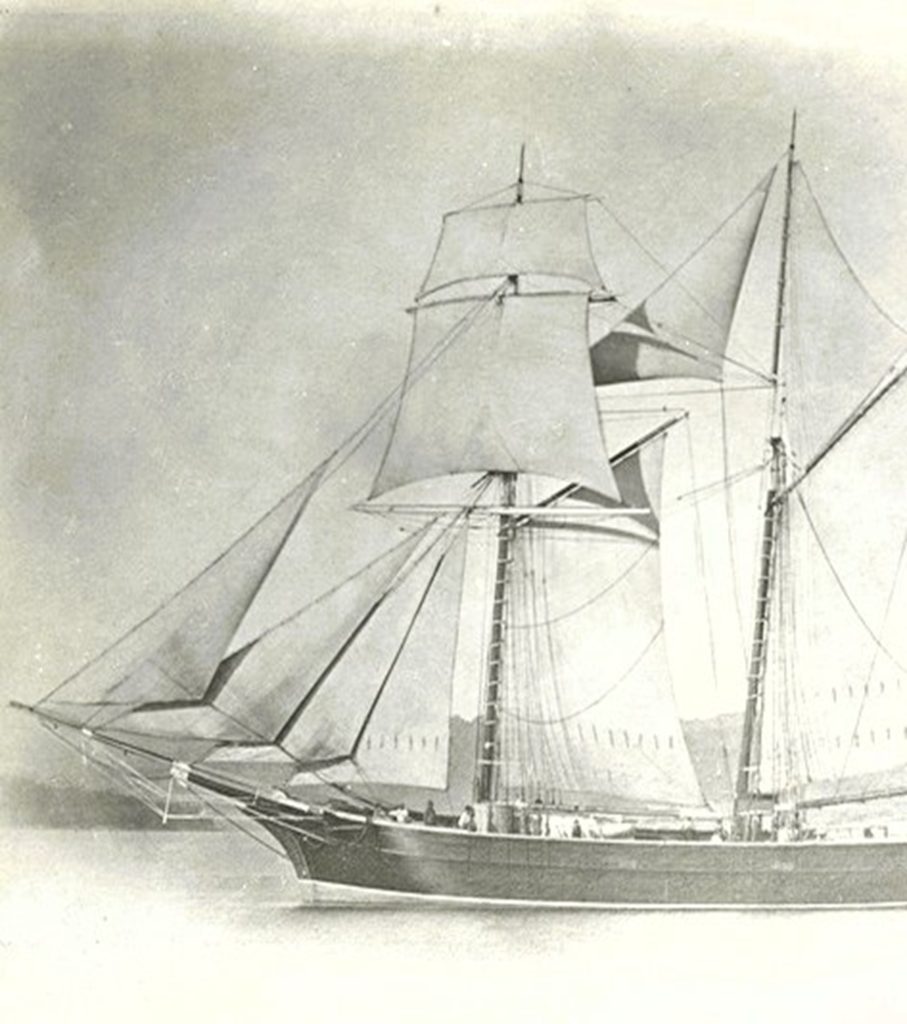

As the 1870’s ended, the construction of the 66-ton wooden schooner, commenced on Mitchell’s Island at Scott’s Point in the Colony of New South Wales for George McEvoy of Cicia (also owner of the ‘Dauntless’), by shipbuilders W McCulloch and J Sinclair. We know that William returned to Sydney just before Christmas 1879 on the ‘Gunga’ from Levuka to supervise the final preparations for the handover of the new vessel, which according to family sources was launched by wife Emma, or possibly daughter Maud. The Sydney Daily Telegraph of 6 July 1880 confirms that it was Captain Petrie’s daughter.

“On Tuesday week last (29 June 1880) a handsome schooner yacht, built to the order of a Fiji firm under special survey, was launched from the building yards of Mr McCulloch, on the Manning River. As she glided off the ways she was christened Windward Ho by Miss Petrie, daughter of the Master, who for years past has been favourably known in the south sea island trade. The Windward Ho is one of the finest pieces of naval architecture that has ever been produced in New South Wales and reflects great credit on Mr McCulloch, her builder. …. This smart craft will be alongside Circular Quay in a few days, and sail for Levuka on receival of stores.“

The ‘Windward Ho’, on which William would be the Master for the next four and a half years (1880-1884), departed Sydney for Levuka on 4 August 1880, with Mrs Petrie and three daughters on board, as well a Miss Jones and a Mr Lennox. According to The Evening News of 23 September 1880 she made the voyage in 14 days. As a result, we now know that the Petrie family arrived in Fiji on 18 August 1880. Three months later, on 22 November 1880, Emma gave birth prematurely to a son John at Tonga Street, Levuka. Sadly, he died the following day.

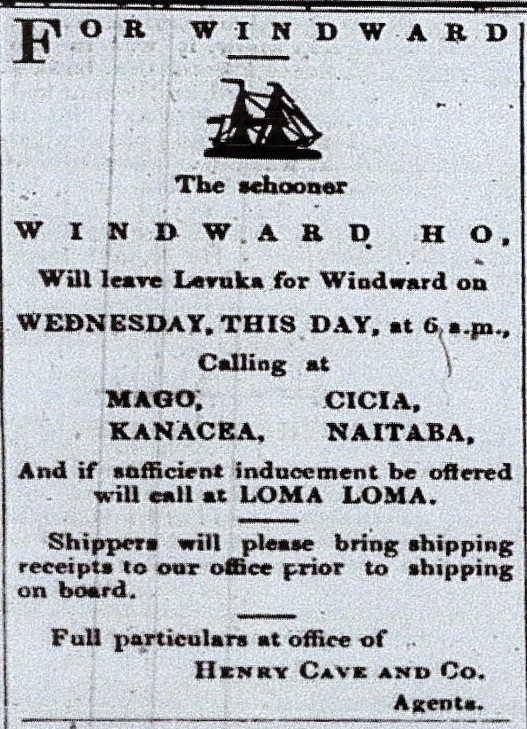

Although the registration of the ‘Windward Ho’ in Levuka by George McEvoy was not completed until 24 February 1881, she had undertaken several voyages under Captain Petrie’s command to what was locally known as ‘Windward’, those islands on the eastern side of the Colony, including Mago, Koro, Cicia, Kanacea, and Naitaba, with Lomaloma and Rotuma offered on inducement. This was a crowded trade and not particularly profitable which, along with the recent loss of the ‘Dauntless’ on the Astrolabe Reef and the approach of the labour trading season, McEvoy responded to a Colonial Government tender for vessels to recruit Polynesian (sic) labourers for the 1881 season.

On 19 March 1881, a report in the Fiji Times states that, “The immigration departments are pushing forward preparations for next season’s labour operations as rapidly as possible, and eight vessels are at present under charter for the service. The fleet is a fine one both as regards tonnage and sailing capacity and is constituted as follows: The Winifred, Meg Merrilies, Tubal Cain, Jessie Kelly, Au Revoir, Windward Ho, Gael and Isabel.”

What constituted a ‘labour trading season’ is not clear, but three voyages a year appeared to have been the norm, and, in exceptional circumstances, four sailings were possible. The duration of each voyage was around three months.

The smaller and more manoeuvrable schooners, like the ‘Winifred’ and the ‘Windward Ho’, were able to recruit in bays and inlets that were more difficult to navigate for larger vessels – a decided advantage along with their speed, wind conditions permitting. Indeed, I discovered that the ‘Winifred’ entered at least two sailing regattas in Auckland. In the race of 1883, for trading vessels over 50 tons, the ‘Winifred’ appears to have protested the award of first place to another vessel and lost. The ‘Meg Merrilies’, prior to her labour recruiting days, held the record for the Auckland to Levuka (1880) run of 5 days and 18 hours.

We know from the National Archives of Fiji that the ‘Windward Ho’ was commissioned by the Colonial Government for three ‘seasons’ and clearly, William’s voyages around the islands were not without challenges.

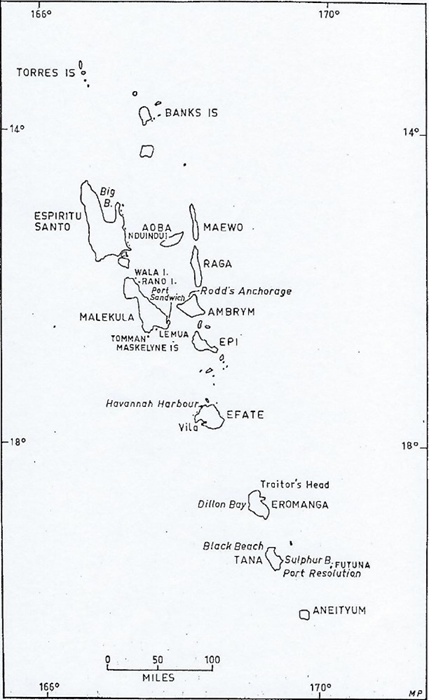

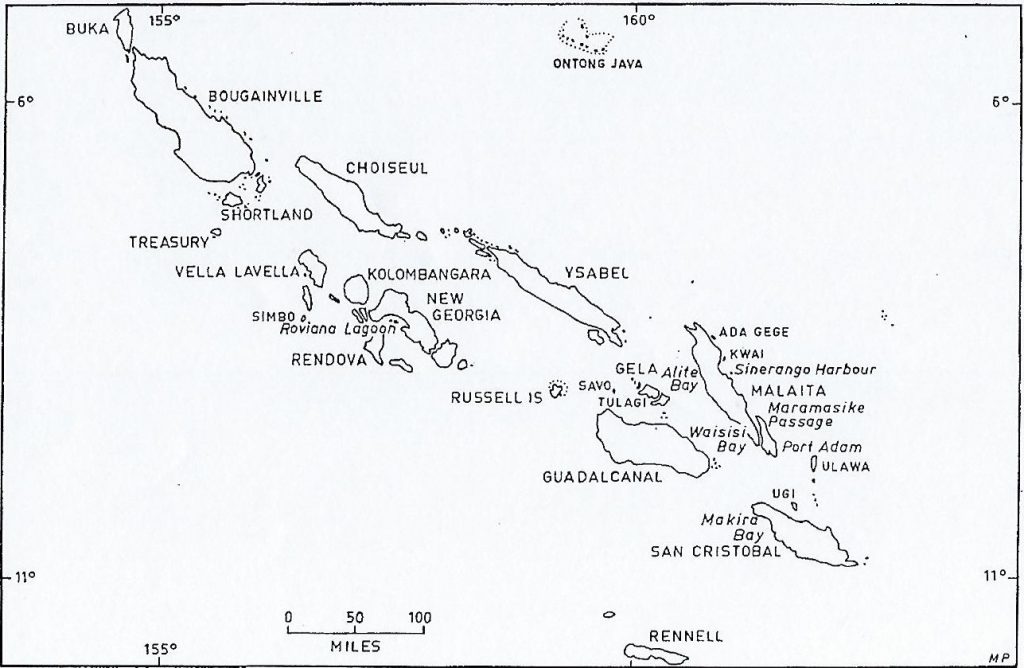

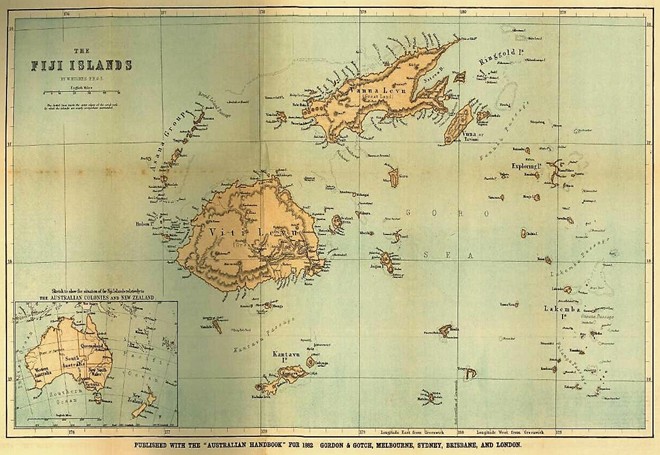

The first voyage of the ‘Windward Ho’ under charter by the Colonial Government departed Suva on 5 April 1881 and was to the New Hebrides. It would be reasonable to assume William had made earlier visits to these islands on the ‘Atlantic’ and ‘Dauntless.’ The ‘Windward Ho’ was fired upon at Pentecost Island (Raga Island as it was locally known, directly north of Ambrym on the map above) and while recruiting, one of the crew, a Fijian, was shot dead. She returned to Suva on 27 June 1881. It does not appear to have been an overly successful venture in terms of the number of new recruits brought to Fiji. The diaries of the Government Agent on board, Mr G L’Estrange, are held by the National Archives of Fiji in Suva.

McEvoy was keen to get the ‘Windward Ho’ back on the high seas as quickly as possible and Petrie went on to complete two further voyages before the start of the 1882 season. The ‘Windward Ho’ departed port on 14 July 1881 and once again headed for the New Hebrides where, according to the Fiji Times, she returned to Levuka on 11 October 1881with 48 labourers – just three days short of three months at sea. According to the Fiji Times and subsequently reported in the Melbourne Argus during November 1881, Petrie had expressed “an increasing difficulty in obtaining labourers and predicts the next seasons recruiting vessels will have to go much further afield, probably to the islands of Bougainville, New Britain etc.”

The ‘Windward Ho’ turned around in 10 days with the voyage this time, in addition to the New Hebrides, including the Solomon Islands, where William secured most of his 39 recruits. She sailed back into Levuka port on 9 January 1882 and once again was re-engaged in the ‘Windward’ trade to fill in the gap between the labour trading seasons.

In 1882 following what appears to have been intense lobbying of the Governor (Des Voeux) by the Planters Association of Fiji (Chairman George McEvoy) and others, labour recruiting requirements were amended, as reported in the Fiji Times, “to better reflect planters needs.” This included an increase in the number of vessels licenced to recruit labour. In a significant departure from the previous year, licences were issued to 13 vessels, all of which were chartered to supply labour to designated private firms, not the Colonial Government. For example, the ‘Lord of the Isles’, ‘Au Revoir’, ‘Loftus’, ‘Mavis’ and ‘Sea Breeze’ were all licenced to recruit for the Colonial Sugar Refining Company (CSR.) Interestingly, the ‘Windward Ho’ was licenced to recruit for its owner George McEvoy, who at the time leased and cultivated a large portion of Cicia Island and parts of Kanacea, the latter in partnership with James Borron.

The ‘Windward Ho’s’ first voyage of the new season departed Levuka Port for Suva via Mago on 17 March 1882 and then onwards ten days later to the New Hebrides and the Solomon Islands with a new Government Agent, Mr Crookes, on board. She returned to Suva on 20 May 1882 bringing 47 labourers from Mallicolo (Malekula on the map above) “being three less than complement” according to the Fiji Times of 3 June 1882, which continued, “She commenced recruiting on 6 April and up to 28 April had 43 recruits – twenty two days out. After that they were not so fortunate and had only got four more in nearly four weeks, owing principally to bad weather. Left for Suva on 24 May, sighted Mount Washington (an 805 metre high volcano located on Kadavu Island) on 29 May and anchored in Suva at noon on 30 May.”

Whilst the ‘Windward Ho’ was away on her second voyage (departed Suva on 4 June 1882), the Mago Island Company Limited acquired McEvoy’s interests in Cicia and the jointly leased property in Kanacea. As a result, indentured labourers recruited by the Petrie, for the remainder of the season, were redirected to the new company’s plantations. McEvoy and Borron were kept on as managers. Of the ‘Windward Ho’s’ four day turnaround and departure from Suva the Fiji Times reported, “Great credit is due to her agents, Messrs H Cave and Co., for the prompt despatch she has received.”

By way of background, a cotton plantation was established on Mago by the Ryder brothers of Australia in 1864. Indeed, Rupert Ryder is reputed to have been an early pioneer in the cultivation of ‘Sea Island Cotton,’ the international reputation of which, and Mago, was greatly enhanced by the award of gold medals at exhibitions in Paris and Philadelphia. Ryder is also said to be one of only two planters who made a profit from cotton in the Colony.

In 1881 the Mango (sic) Island Company Limited was registered in Melbourne “to purchase Mago (freehold land) and carry on the plantation there.’” Directors included Edward Langton, a former Treasurer of the Colony of Victoria, James (later Sir James) Lorimer, local businessman and politician, Herbert Henty, businessman, William Kerr Thompson of James McEwan and Company and the Ryder family who retained a one fifth interest in the Company. During the following year the Company extended its operations beyond Mago.

When the bottom fell out of the cotton market, cane sugar was added to the crops grown on Mago and a mill built on the island. It is here that William appears to have developed a strong friendship with James Borron, a fellow Scot and Manager of the sugar mill, which opened in May 1884 and concluded its first crush in August of that year. It is also noteworthy that one of the clerks engaged by the Ryder Brothers, and presumably the Mago Island Company, at the time was Herbert Edward Ambler, our Great-Grandfather, who married William’s daughter Maud Wilhelmina (Minnie) Petrie in 1892.

At the height of its operations the Mago Island Company boasted a thriving community of 70 expatriates and over 1,000 indentured labourers, including 80 Girmitiya recruited following the introduction of the new crop. At one point, the area under cane on the island was purported to be the largest in the South Pacific. In addition, the supporting infrastructure included seven miles of tramways, principally horse drawn, with the capacity to deliver 90-120 tons of cane to the mill each day during the crushing season, as well as servicing the wharf. Alas, the confidence in the Mago Island Company’s future, expressed by its directors, was sadly misplaced and short lived.

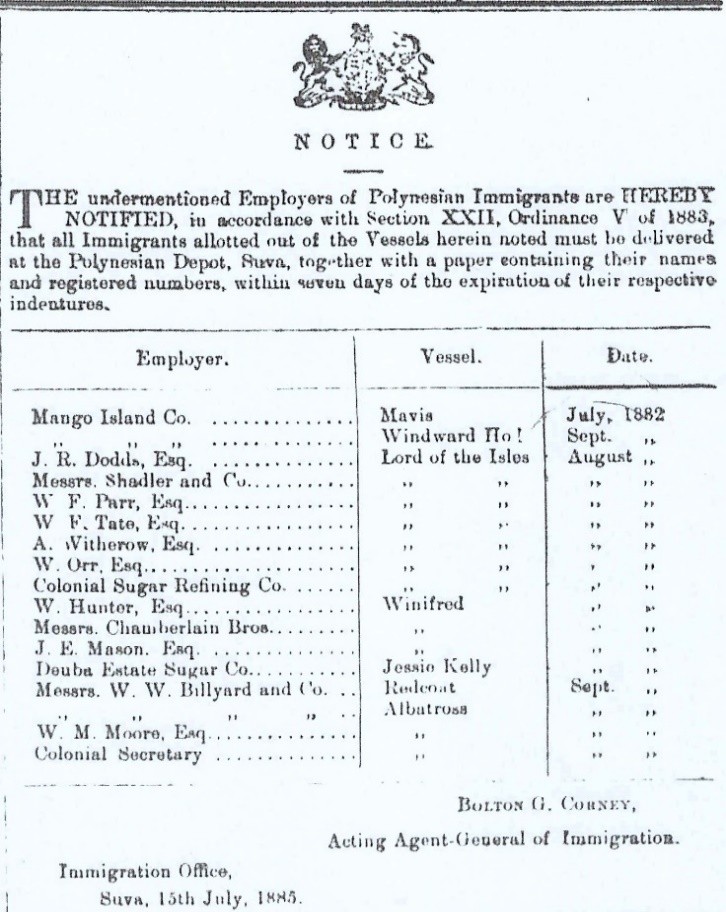

As and aside, several of the photographs taken on Mago by the Burton Brothers in 1884 are more than likely to have included images of labourers brought to the island a year or two earlier by Petrie from the New Hebrides and Solomon Islands. Towards the middle of the 1880’s the Fiji Royal Gazette regularly published a Notice to Employers of Polynesian (sic) Immigrants notifying them of their obligation under Section XXII, Ordinance V of 10 April 1883 to return their labourers at the expiration of their respective indentures. The names of the employers, the vessels engaged in the recruitment process and the month of arrival in the Colony are all specified in these Notices. The ‘Windward Ho’, for example, made two deliveries of indentured labour to Mago in 1882.

The return of Polynesian (sic) labour was managed centrally out of Suva. I discovered that later Notices in the Fiji Royal Gazette referred to “… all surviving immigrants”, which sadly acknowledged the horrendous mortality rate among those working in the Colony, with some estimates as high as 20%. Indeed prior to the commencement of the 1883 season, the Colonial Government, in the face of fierce opposition by the Planters Association of Fiji, legislated to improve the lot of the labourers being recruited for the Colony’s plantations.

Association members also took great umbrage at the random checks of the conditions under which labourers were being kept, with the inspections often unannounced and usually by night!

Petrie gave an account of his second voyage in the 1882 season to the Suva Times which appeared on 16 September 1882, two days after his return from the New Hebrides. Petrie disclosed that, “On 9 June landed boats crew at South West Bay, Sandwich and engaged fresh boat crew next day.” South West Bay is situated on the island of Malekula and the reference to Sandwich probably refers to Port Sandwich, not the island immediately South, also known as Efate – both port and island were named by Captain James Cook after the Earl of Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty. Petrie continued, “Commenced recruiting on 11 June, but did not make a break until 26 June when engaged four at Pentecost. No further access until 13 July when we got twelve men and women in two days; fine weather throughout from first starting up to this day when weather set in bad and continued, only picking up and occasional one or two here and there all over the group. Up to 2 August recruited 45 people. On 28 August gave it up owing to continuous bad weather with much rain; started to work southward. On 30 August anchored in South West Bay, filled up with yams, wood and water and sailed next day on route to Suva. On 4 September got becalmed five miles off Anietenim (Aneityum in the above map) and was boarded by Captain Freeman, who reported the French cutter Port of Villa had been pillaged by natives on the lee side of Santo, and the captain, owner and four crew murdered. A French man-of-war had called in a few days after but not a native was seen during their stay. They put a crew on the pillaged vessel and sent her to New Caledonia. Had strong ESE winds throughout the passage until 10 September when it fell calm and afterward veered northward. Sighted Mount Washington at 2:00am on 14 September and arrived in Suva at 3:00pm with 45 recruits, all well.”

In what appears to have been a first for William and his crew, they completed four sailings in search of labour during the 1882 season. After another quick turnaround the ‘Windward Ho’ departed late September, once again for the New Hebrides and returned to Suva on 21 December with 53 new recruits.

The perils of the trade continued when in January 1883 whilst in the Solomon Islands, on Petrie’s fourth voyage, that the crew of the ‘Windward Ho’ was fired upon. Two recruits were wounded, and a Mr Coll and the Boatswain were transferred to the schooner ‘Winifred’, one suffering from a bullet wound and the other from a spear thrust.

As a new recruiting season approached the Colonial Government appeared to have distanced themselves from direct commissions and chartering vessels for recruiting purposes, except on an ad hoc basis, and shifted that responsibility to owners and their agents. The Department of Immigration continued to issue licences to recruit, provide Government Agents for each licenced vessel and be responsible for the return of time-expired labourers. This change of practice was apparent by the growing number of advertisements in the Fiji Times by owners and ships agents touting for business from employers seeking allotments of Polynesian (sic) labour and the despatch of suitable vessels. Henry Cave & Co, A.M. Brodziak & Co and F.W. Witham were particularly active in this space.

The 1883 season got off to a slow start with the ‘Albatross’ first to depart Suva on 1 April 1883, quickly followed, on the same day, by the ‘Winifred’, ‘Windward Ho’ and ‘Sea Breeze.’ The ‘Lizzie Davis’ was delayed awaiting spars from Sydney and the remainder of the labour fleet in various stages of readiness.

These vessels included, the ‘Marie’, ‘Christine’, ‘Meg Merrilies’, ‘Hally Bayly’, ‘Midge’, ‘Omaru’, ‘Minnie Hare’ and the ‘Falcon.’ It turned out that Colonial Government had issued the same number of licences as the previous year.

The ‘Windward Ho’ departed Suva with 57 return labourers to land at Ambrym Island. Captain Petrie reported, “Completed return labour to land on 15 inst. (April) and started to recruit the next day. All going well, until 8 May when Boat-steerer, James Ludlow, left the vessel and went onshore six miles west of Tonoa to pick up some locals to assist with recruitment.” According to Petrie, “A messenger came to the beach town that afternoon stating that James Ludlow had been killed and told us the name of the two men who shot him and the towns they belonged to. Waited three days, got no further information, and left. Worked all over the group continuing fine weather throughout, until 27 June having obtained 43 adults, when the weather set in stormy which continued until making land. Wind from ENE To ESE, blowing hard accompanied with much rain. Went all the way under reefed canvass arriving in Suva on 26 June.” This account was assembled by me from articles in the Fiji Times and Auckland Star of 18 July 1883.

The following voyage of ‘Windward Ho’ departed Suva on 5 July 1883 for the New Hebrides, with Government Agent T Fitzpatrick on board and returned on 3 October 1883. By all accounts nothing of an eventful nature occurred while at sea.

The same cannot be said about the final voyage of the ‘season’, as far as we have been able to determine. The ‘Windward Ho’ made a quick turnaround (seven days) and departed Suva for the Solomon Islands on 10 October 1883. On his return on 17 January 1884 Captain Petrie, and his Boatswain, James Cadogan, faced a charge that they “did on 4 December 1883 at Malayta (Malaita) murder one Eyami.” The case (Regina v Petrie and Cadogan) came before the High Commissioner’s Court for the Westen Pacific in Suva on 4 February 1884 and was presided over by the Chief Judicial Commissioner, Sir Henry Wrenfordsley.

What follows is an amalgam of several articles which appeared in Trans-Tasman newspapers under various headlines including ‘Affray on a Labour Schooner’, ‘A Homicidal Maniac’ and ‘Justifiable Homicide.’

“One of the recruits appeared suddenly to be seized with a frenzy and attacked all hands with a butcher’s cleaver seriously wounding eight or ten men. The deck of the vessel was described as looking like the floor of a slaughterhouse. Seeing Petrie and his weapon the man took refuge in the hold and though wounded was armed with poison arrows and spears and considered dangerous. After consulting the Government Agent (T Fitzpatrick) on board, the Boat-steer was ordered to disable him with a rifle shot, through a hole bored in the bulkhead. He was hit in the shoulder and died two days later, whether from the shot or wounds received in the melee, is not clear. Testimonies were given to Captain Petrie’s humane conduct and extreme care of the dying and wounded during the investigation that followed. In court the Government Agent stated his belief that it was necessary for the general safety of all on board that this man be shot. Sir Henry Wrenfordsley, considering those who had been wounded and the sixty persons placed in extreme peril, concluded the act was justifiable and acquitted the accused.’

Levuka Public School, July 1884 (Source: Burton Brothers Studio, Dunedin. Alfred Burton. Purchased 1943. Te Papa Museum of New Zealand)

I often wonder if William ever got to see his family in Levuka. For example, he would have missed the annual distribution of prizes at the Levuka Public School on Wednesday 19 December 1883 where his three daughters received awards. Minnie (aged 15) second girl in the Fourth Class exam; Dora (aged 9) for General Improvement and Florrie (aged 6) for Good Behaviour in First Class. Dora also won a needlework prize the following year.

I add a brief, but important, historical aside about the Intercolonial Convention that was held in Sydney in November and December 1883.

William Petrie along with over 170 prominent colonists (a veritable who’s who of Fiji’s nascent business community), in expressing their dissatisfaction about the way the Colony was being administered, sought to be included in any federation of Australian colonies that was being considered by the delegates to the Convention, which interestingly also included the Premier and Colonial Treasurer of New Zealand. The ‘Memorial’ as it was styled, but better described as a petition, is an interesting read and among the many grievances was one “that your Majesty’s subjects in this Colony are discontented and grieved that all right of being represented or heard in the Councils of this colony is denied to them, and that they have no voice in the administration of the colony, the enactments of its laws, or the public expenditure.” Perhaps no one should be surprised that the petition failed!

Undeterred, a year later another request, initially to the Warden (Mayor) was raised by the residents of Levuka as to “the desirability of annexing Fiji to New Zealand.” Although Petrie was missing from the list of concerned citizens this time, our Great-Grandfather Herbert Ambler numbered among the signatories. This Petition was formalised on 6 May 1885 and addressed “To the Hon. Speaker of the New Zealand House of Representatives in Parliament assembled.” The outcome of these representations appeared to meet the same fate as the earlier ‘Memorial’ to the Intercolonial Convention, with the Colonial Office, to which it was referred, said to have more pressing issues on its plate. These resilient early settlers apparently would not take ‘no’ for an answer and quickly set up a committee to investigate the potential for joining the Colony of Victoria!

After the trial ended in February 1884, it appears that Petrie was relieved of his command of the ‘Windward Ho.’ Shipping records show she departed Suva on 30 March 1884 with a new Master at the helm by the name of Hughes, a new Government Agent (Pilkington) and 37 returnees for the New Hebrides.

William did however secure another command, albeit for one sailing, on the smaller 43 ton schooner and known labour trading vessel the ‘Midge’ and departed for the Line Islands (British Western Pacific Territories, made up principally of the Gilbert and Ellis Islands and some of the Marshall Islands) in late May 1883. This does not appear to have been a successful voyage. The Fiji Times reported on 13 August 1884 that, “The labour schooner Midge arrived in Suva on Saturday afternoon (9 August) with 31 recruits, having been absent since 31 May. She will not go again.” The ‘Midge’ returned to the inter-island trade with a new Master, travelling to Rabi, Rotuma and ports on Viti Levu, including Suva and Ba. The ‘Minnie Hare’, a participant in the 1883 season, had also done likewise.

The ‘Windward Ho’, under Captain Hughes’ command, arrived in Suva on 18 August with only 40 recruits after four and a half months at sea, with the decision apparently taken a month earlier to withdraw her from the labour trade. “The well-known clipper schooner” described as “specially constructed for the Island Trade, with fine saloon accommodation” had been offered up for sale or charter by the vessel’s Agent, Henry Cave & Co., in the Fiji times of 16 July 1884.

In the meantime, Petrie was engaged as Master of the Mago Island Company’s 45 ton schooner the ‘Eastward Ho’, another former labour trading vessel with most of his voyages regularly taking place between Levuka, Mago and Suva. No more New Hebrides and Solomon Islands for William (or at least that is what I thought) and hopefully he had more time for family than in previous years, despite a heavy sailing schedule.

The departure of the smaller vessels such as the ‘Midge’ and ‘Windward Ho’ from the labour trade was a sign of the times. The increased difficulty in securing new recruits and the time taken to do so was eating into the viability of these voyages, especially when compared to the carrying capacity of the larger vessels (over 50 tons) such as the ‘Albatross’, ‘Christine’, ‘Winifred’, ‘Meg Merrilies’, ‘John Hunt’ and ‘Sea Breeze.’

Agents for some of the larger vessels were also considering their options, for example, the ‘Christine’ departed Suva on 8 November 1884 for the New Hebrides and after discharging her 115 returnees left the trade. In the Fiji Times she was said “to proceed on a trading trip.” The ‘John Hunt’ also took a short break, making a detour to New Guinea where its owner was thinking of establishing a presence, before embarking, in the new year, on another voyage to the Solomons and the New Hebrides to return and recruit labour The ‘Winifred’, absent for nearly four months, berthed in Suva on 12 November 1884 with 89 labourers, where the crew’s recruiting efforts were severely hampered by sailing under an arms and ammunition prohibition recently introduced by the Colonial Government, placing them at a distinct disadvantage with Queensland vessels operating with no such restriction. The ‘Winifred’ was withdrawn from the labour trade by her Agent and languished in Levuka Harbour for several months. Her Master, John Meredith, assumed command of the ‘Meg Merrilies.’

Ironically, Henry Cave & Co sought compensation from the Colonial Government of £500 for the loss incurred on items (read arms and ammunition) they were contracted to supply to pay off Polynesian (sic) labourers. According to the Company, “When the tender was accepted nothing was said about the contemplated prohibition.”

The increasing number of Girmitiya arriving in the Colony, estimated at around 4,000 between 1879 and 1884, was addressing the acute labour shortages of previous years and this too had consequences for recruiters working the islands to the west of the Colony.

It is important to recognise that those bringing Girmitiya to the Colony often faced similar challenges to some of the labour recruiters of the western Pacific with inexperienced and incompetent crews and a lack of familiarity with navigating coral atolls and reefs. As was the case with one of Fiji’s worst maritime disasters when the Indian immigrant ship, the 1,000-ton iron sailing ship ‘Syria’, carrying 497 indentured adults, children, infants and a crew of 43 from Calcutta ran aground on Nasilai Reef (off Nasilai Village in Nakelo, Tailevu) on 11 May 1884. Tragically fifty six immigrants and three crew drowned.

Towards the end of 1884 there were only two vessels recruiting in the New Hebrides and Solomon Islands. Discounting the schooners ‘Christine’ and ‘Glencairn’ returning time-expired labour only, there was the ‘Sea Breeze’ and the ‘Meg Merrilies.’ Although the ‘Meg Merrilies’, had been quarantined in late September, following the loss of 19 recruits to dysentery and chickenpox and having been offered up for sale or charter at the same time as the ‘Windward Ho’, she returned to the labour trade on 22 December 1884.

Some context is appropriate regarding the two New Zealand built vessels, the ‘Winifred’ and the ‘Meg Merrilies’ mentioned above. Both the 79-ton wooden schooner ‘Winifred’ and 135-ton wooden brigantine ‘Meg Merrilies’ plied many of the same routes as the ‘Windward Ho’ and were, for a time, under the command of John Meredith. Meredith secured his various seaman’s tickets in Sydney (Master’s Certificate of Competency issued on 30 January 1877) and spent several years working in Australian coastal waters servicing ports like Maryborough, Queensland where he would have met many of the crews and Masters of labour recruiting vessels, including some from Fiji. There is little doubt that Petrie and Meredith were known to each other.

The Melbourne Argus of 17 January 1885 reported that “The schooner Winifred has been in the Fiji trade for over six years, during which time she has recruited 1,500 men and returned about 1,000. No case of mortality has ever occurred among her people and no complaint has ever been lodged against her. She has been sailed by several Masters, but for over half the time by John Meredith, who was formally in government service of Fiji and to whose good character testimony is borne by Bishop Selwyn and the captains of several of Her Majesty’s ships of war for whom he has repeatedly acted as guide and interpreter. The Winifred has always filled up well, because the vessel and the captain are so well known, and she has regularly made three trips every year returning with her full complement.” On her last voyage. as recounted earlier, she sailed under a new arms prohibition and returned little more than half full. Meredith discovered that Queensland vessels were trading not with Tower muskets, as formerly permitted by Fiji, but with Snyder rifles. The Argus continues ‘realising how thoroughly Fiji had been handicapped, the agents of the Winifred had withdrawn her from the trade. There are now but two vessels recruiting for Fiji exclusive of one in which the Government has since placed Captain Meredith (the ‘Meg Merrilies’) and dispatched him to recruit labourers for government service.’ A similar piece appeared in the Auckland Star of 4 December 1884.

These reports explain why, throughout the 1880’s, the Colonial Government seems to have been more favourably disposed towards Meredith for their commissions, rather than some other sea captains.

John married his first cousin and our Great-Aunt, Emma Goldfinder (taken from the name of the ship bound for Melbourne, in the Colony of Victoria, on which she was born) Ambler, sister of Herbert and Lucy. After 10 years in the Colony the family, including Emma, returned to England on the death of her father, George, from tuberculosis where she subsequently trained as a teacher and became a governess. My cousin John Thomson speculates that Emma was already friendly with John Meredith before his departure for the Colony of New South Wales and that their families may have actively discouraged this relationship. As it transpired, Great-Aunt Emma appears to have set sail from Plymouth for Sydney on board the ‘Samuel Plimsoll’ in April 1883, as an assisted immigrant (presumably paid for from her income as a governess or with some help from Meredith). Where she lived and what she did for the three years that followed remains a mystery. Did she base herself in Sydney? Perhaps she joined her brother Herbert, by which time he had left Mago Island and was living in Levuka or did she take up residence in Suva?

We do know that she and John were married in Suva on 16 July 1886 (no notice found in the Fiji Times) and that a daughter Frances (Fanny) was born on 2 August 1887, also in Suva. The first announcement in the Fiji Times of the birth of the Meredith child mistakenly referred to a son and was corrected in the next edition.

We have recently discovered that our other great aunt, and Emma’s younger sister, Lucy Harriet Ambler also made her way the Colony and married Herbert George Brown ACA on 3 August 1888 at the Nasese residence of the groom’s brother, Leslie Edward Brown, Principal and Resident Partner in the firm of Brown and Joske. The groom at the time of his wedding was an accountant employed by the Audit Office of the Fiji Civil Service. According to family sources Lucy and her husband chose to settle in England. Sadly, I have since discovered that only Lucy did so. Herbert died on 11 May 1890 in Sydney where he had sought rest and recuperation from a long standing illness at the Grand Coffee Palace temperance hotel. He was 34.

John’s last reported return to Suva port on the ‘Meg Merrilies’ was in April 1890, and soon thereafter he accepted the position of Master of the ‘Eastward Ho’, previously owned by the Mago Island Company and sailed for several years by Captain Petrie. There is also evidence that the owner of the ‘Eastward Ho’ was trying, I suggest unsuccessfully, to diversify his business by offering charters. In fact, I was surprised to learn from a distant Meredith cousin that John’s half-brother, William Russell Meredith, promoted this opportunity in the local media in England. I am aware of two repatriation and recruitment voyages undertaken by Meredith to the Line Islands via the New Hebrides and two to the Line Islands only between July 1890 and December 1891. On his final quest to the Line Islands for recruits, which departed Suva in October 1891, John reported that finding 40 labourers had proved difficult due to new arrangements introduced by local missionaries trying to disrupt the trade. Again, I speculate that he had, before embarking on this voyage, already accepted an offer to work for the Protectorate of British New Guinea. It was Dr William, (later Sir William) MacGregor, formerly Chief Medical Officer (during the measles epidemic of 1875), Treasurer, Colonial Secretary and, at times, acting Governor of the Colony of Fiji, who convinced John to leave Suva. Macgregor, who had assumed the position of Administrator (later Lieutenant Governor) of British New Guinea in September 1888, chose to invite a few trusted friends from Fiji to strengthen administrative structures and bring some semblance of law and order to the Protectorate.

Shipping records show Meredith departed Suva on the ‘Clansman’ for Auckland on 8 January 1892, presumably on route to Brisbane, possibly via Sydney, where he took up his initial appointment as First Officer on the Protectorates new 411-ton steam powered yacht, the ‘Merrie England’ (built in 1888 by Ramage and Ferguson of Leith.) The vessel was in dry dock at the time and about to undergo sea trials.

In July 1894 Meredith was appointed Head Gaoler of the Port Moresby prison established by MacGregor and Overseer of Works. In his book ‘Some Experiences of a New Guinea Resident Magistrate’, Captain C A W Monckton recalls meeting Meredith on the ‘Merrie England.’ “Meredith was taking a gang of native convicts down to Sudest Island (in the Louisiade Archipelago); they had been lent by the New Guinea Government to assist in making a road to a gold reef discovered there which was now being opened by an Australian company. It was here that he (Meredith) and many of his charges left their bones.” On 17 June 1897, the Sydney Morning Herald brought news “of the death of Captain Meredith when he is attacked with fever at Sudest Island (consumption supervening), causing his death on 17th May last. The deceased was especially successful in the Fiji labour trade where he obtained the goodwill of all.” John’s death was also included in the ‘British New Guinea Annual Report to 30 June 1897’ where he was described as someone “who took a deep personal interest in each prisoner under his charge; and by firm, kind treatment maintained excellent discipline, while by regular work hours, and the use of the English language he imparted to the prisoners a useful and valuable education. He maintained them in good physical condition, clean skinned, and as contented as men in such circumstances could be.”

MacGregor went on to be Governor of Lagos (1899-1904); Newfoundland (1904-1909) and Queensland (1909-1914) and died in December 1919 in England. Two suburbs in Australia are named after Macgregor, one in Brisbane and the other in Canberra. Meredith’s successor as Master of the Brown and Joske owned ‘Meg Merrilies’, George Archibald Johnson, who departed Suva on 10 May 1890, was found guilty of gross negligence for stranding his vessel twice during the voyage to the New Hebrides and Solomon Islands and in November of that year had his Certificate of Competency suspended for six months. Allegations that Johnson was drunk on both occasions were, according to the Police Court, not substantiated by the evidence. The ‘Meg Merrilies’ made four more voyages to the New Hebrides and Solomon Islands to return time expired labourers and to recruit between January 1891 and December 1892 under Captain Dillamore before departing on 2 January 1893 for Sydney and to be sold. She ended her days as a pearl lugger on the far north Queensland coast and sank off Cape Melville during a cyclone on 4 June 1899.

I had mistakenly thought that Aunt Emma and young daughter remained in Fiji given the lawlessness of the Protectorate and the presence of extended family members in Suva. Thanks to back editions of the Fiji Times, I discovered that Emma had instructed J C Smith & Co to auction her goods and chattels at the family residence on the Extension in Suva in late October 1894 which led me to speculate that John had petitioned William MacGregor for a land-based job in Port Moresby so that family could join him. That job being Head Gaoler and Overseer of Works, mentioned above, which he assumed in July 1894. The other compelling evidence for Emma having left Suva is the death of her mother, Penelope Ambler, in Port Moresby on 16 April 1895. However, we do know that Emma and Frances did return to England sometime after John’s death and were recorded in the 1901 Census as residing at 1 Albert Road, Southport, Lancashire. This was the location of a boarding school run by Emma’s sister-in-law Mary Walmsley (nee Meredith) and where Frances, aged 13, was enrolled as a scholar. It does appear that Emma, along with Frances, returned to Fiji at or around the time of her brother Herberts death, as I have sighted a record of two Merediths about the right ages travelling from New Zealand via Australia and possibly onwards to the UK in 1909. Again, we know from the 1911 Census that Emma was living with her spinster Aunt Anne Ambler in Shrewsbury, the administrative centre of Shropshire. Frances’s whereabouts at that time remains a mystery. Emma died in 1950 at the age of 97. Her residence at the time was given as 7 Coton Crescent. Frances, a nurse by training and unmarried, predeceased her mother. Thanks to research undertaken by another distant cousin, Catrin Meredith, we have recently become aware that there are three stained glass window panels in memory of Frances, crafted by yes, another cousin, Joyce Meredith, located in St Mary’s Church, Shrewsbury. The dedication reads, “In memory of Emma Frances Meredith April 29th 1933 RIP.”

The ‘Windward Ho’, in the absence of a buyer or a new charter, sailed from anchor in Levuka to Sydney, arriving on 24 November 1884, where she was again offered for sale by McEvoy, now residing in Melbourne and formerly of Mago and Cicia. She was eventually purchased by the notorious labour trader Captain Donald McLeod during a visit to Sydney in 1885 around the time he divested himself of his interest in the French New Hebrides Company.

The ‘Windward Ho’ was now sailing under a licence issued by the Colony of New South Wales for the purpose of “procuring beche-de-mer and pearl shell” but in reality employed for recruiting labour, except for a brief pause in 1887 when McLeod used the schooner to search for remnants of the La Perouse expedition, wrecked a hundred years earlier on the reefs of Vanikoro in the Solomon Islands. Later, in 1890, the ‘Windward Ho’ was caught recruiting underage labourers in exchange for firearms at Pentecost Island (Raga), and without its ship’s papers. McLeod was not on board at the time. The charges were proved with the Master fined £20 by the Joint Naval Commission, based in Noumea.

Sir John Thurston, Governor of Fiji and High Commissioner for the Western Pacific, in a letter to Lord Knutsford (Secretary of State for the Colonies) dated 22 February 1891 wrote, “There are no satisfactory means of controlling the actions of men like McLeod, who are adept at evasion, who place their ships occasionally and nominally under the French or American flag. They are not fit to be licenced.”

It appears that the schooner, now operating out of Havannah Harbour on Efate Island in the New Hebrides, may have seen out its days in that port. Beyond that, I could find nothing more about the fate of the ‘Windward Ho.’ McLeod died in Noumea in late 1894.

Sometime late in the previous year the Fiji Times, The Suva Times, shipping intelligence reports as well as some government documents had begun to refer to the ‘Winifred’ by it registered name, with ‘e’ displacing the second ‘i’ of the name and I will do so in future references to this vessel.

Petrie continued in the employ of the Mago Island Company and on 20 January 1885 returned to Levuka from Mago with the Ryder family as passengers as well a few labourers destined for Suva to face criminal charges before the Supreme Court. On route to Suva, according to the Fiji Times, “Captain Petrie had a very heavy time of it and had to put back. At one time a waterspout passed unpleasantly near to the vessel and at another her sails were blown away. Petrie was close to the reef all Sunday but could not get to landfall for the heavy weather and had to stand off until Monday morning.”

The new year saw an increased focus by the Colonial Government on the return of time-expired labourers to their place of recruitment, with less emphasis on securing new Polynesian (sic) recruits. Indeed, there were few vessels available in 1885 to fulfil this role. Labour trading vessels on the seas or scheduled to depart in the new year included the ‘Meg Merrilies’ on route to the New Hebrides and the Solomon Islands with 170 returns. The ‘John Hunt’ sailed from Suva for the same destinations with 81 returnees on board at the end of January. The ‘Sea Breeze’, having returned 112 labourers and been absent for four months berthed in Suva in February and then sailed for Sydney in March as the Fiji Times reported, “Employment can no longer be found in the labour trade.” The ‘Albatross’ returned to the trade at the end of February departing Suva for with 110 returns. The ‘Sea Breeze ‘, ‘Christine’, ‘Meg Merrilies’, ‘John Hunt’ and ‘Albatross’ were the last remnants of a flourishing labour trade that had lasted over two decades. Later in the year the ‘Sea Breeze’ went missing on route to Sydney and according to Fiji Times of 21 July 1885, “It is now nearly four months since sailing from this port and no tidings of her have since come to hand. There is therefore no room for hope that she has escaped serious accident, if not utter disaster.” In another report the ‘Christine’ “had been condemned at the Solomons and sent to New Zealand.”

And then there were three, the ‘Meg Merrilies, ‘John Hunt’ and ‘Albatross’ left, which was not surprising given the increased reliance on indentured labour from India, the arms and ammunition prohibition and the parlous state of the local sugar industry resulting from a worldwide drop in prices. The Colonial Sugar Refining (CSR) Company Ltd, which established its first mill at Nausori in 1882, was in the process of taking over a number of the failing sugar estates belonging to many of the early Rewa settlers and at least two mills ceased operations in 1885 – the Rewa Plantation Mill located mid Rewa and another in Navua owned by Sharp, Fletcher & Co Ltd, with the small Pioneer Sugar Mill, one of the earliest established in Rewa, removed to Dreketi.

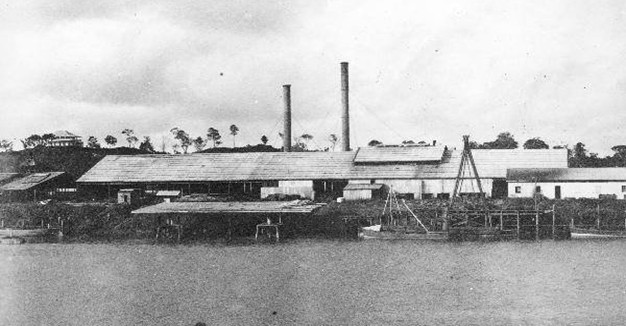

CSR’s Sugar Mill at Nausori on the Rewa River (Source: ANU, Canberra)

Petrie continued his Levuka, Mago, Suva runs, which remained uneventful until the Fiji Times of 25 July 1885 reported, “News to hand from Suva, by the Rockton, of a very sad accident which is feared has there occurred. Among the Rockton’s passengers from Sydney was a Mr. Dawson, who had formerly been in Fiji and had been engaged as an overseer at Mago and as a government labour agent. He was returning to the Colony with the means to push his fortune as a planter or trader. On landing in Suva, he met and old friend in Captain Petrie of the Eastward Ho and as they remained in company till late in the evening, the captain took him off on board his own ship. In the morning his hat was found on the deck, the boat had not been touched, but Mr. Dawson had not been seen when the Rockton left. As the place is so small that he could hardly escape observation, it is likely that he must have walked overboard in the darkness and been drowned. Search had been made for his body, but it had not been found.”

There are no reports of an inquest or what Petrie did next, but it appears he did not return to Levuka on the ‘Eastward Ho’ until late November 1885. Perhaps he was holed up on Mago, sailing to and from Suva and points windward? Again, I cannot verify that this was the case. Interestingly, the Fiji Times reported in December 1885 that, “The schooner Winefred is now fitting out for a labour cruise. She will leave at an early date under the command of Capt. Petrie and will recruit men for the Mago Island Company.” The ‘Winefred’ had been laid up and idle in Levuka harbour and at Waikorokoro for thirteen months.

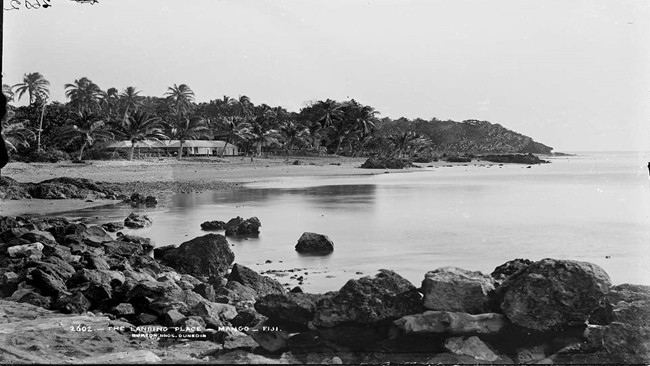

The Jetty Mago Island, June – July 1884 (Source: Burton Brothers Studio, Dunedin. Alfred Burton.

Moving into a new year the concept of a recruiting season no longer seemed applicable with vessels chartered on an ad hoc basis and only when a full complement of returnees was available. Sailing times had become somewhat haphazard, with multiple drop-off destinations, the scarcity of new recruits and the arms prohibition adding to the time the vessels were at sea and away from home ports.

After a thorough overhaul and refit and a false start, the ‘Winefred’ departed Suva on 30 January 1886 for the New Hebrides with 94 returns and a licence for 79 recruits. On board a Mr A Coates, Government Agent.

The remaining vessels in the labour trade left Suva early in the new year with full complements of time-expired labourers and licences for considerably less new recruits. None of the vessels, the ‘Meg Merrilies’, ‘Albatross’, ‘Elizabeth’ and ‘Christine’, met their licenced number of recruits.

Whilst the ‘Winefred’ was away, Levuka was desolated by a severe hurricane which began on the eve of 2 March and increased in fury on the next day with lives lost and the town partially destroyed. Of the 15 vessels taking refuge the night before at Waikorokoro only seven survived, with sadly considerable crew losses. The ‘Eastward Ho’ was caught up in the storm and lost her mast on route to Mago from Cicia. She almost did not make it back to Mago and only did so under a jury mast. The trials and tribulations of Captain Place and his crew were published in the Fiji Times of 31 March 1886.

The ’Winefred’ docked in Suva on 7 June 1886 after five months at sea. Captain Petrie reported (Fiji Times of 12 June 1886, partially abridged), “That he left Suva Harbour on 30 January with 94 returns for New Hebrides: and to recruit a full complement if obtainable, failing that to proceed to Solomon Islands. On the same evening took departure for Beqa, sighted Ambrym on the morning of 11 February and anchored same evening at Toadstool Bay, Pentecost. Landed 53 returns on the islands of Pentecost, Maralava, Vanualava, Santa Maria, St. Philip’s Bay and Santo. Had a succession of light winds, calms, and variable weather for several days in succession. It took us twelve days to land one at Pelin. Up to 25 March had landed all returns excepting one man for Mallicolo and 34 recruits on board. Worked the islands of Santo and Mallicolo and only obtained two recruits on each island, since muskets and ammunition were stopped, they do not care for recruiting. Sighted Christine on 24th steering towards Mallicolo. On 25 April had 53 recruits and by 12 May that number had increased to 73. With the weather unfavourable for further recruiting, proceeded southward. Took on board yams, firewood and water. On 22 May took final departure with strong trades from E to ESE, passed to windward of Tanna on 25 May with heavy seas until making (sighting) land on the morning of 31st May, when we tacked ship off Viwa. Very light baffling airs, chiefly from East. On 4th June tacked ship off Lekuri and arrived at Suva on 7th June with 73 recruits, all well.”

Two further detailed accounts, one by Bissett of the ‘Albatross’ and the other by Meredith, of the ‘Meg Merrilies’ appeared in the Fiji Times of 24 July and 31 July 1886 respectively following their return from the New Hebrides and Solomon Islands.

The ’Lord of the Isles,’ which was about to rejoin the labour trade, drew some unfavourable publicity in the Suva Times of 14 August 1886, whether it was an editorial piece or information anonymously provided by the Planters Association, has been difficult to determine. It read, “Illustrative of the vexatious obstructions placed in the way of planters, we mention that the Mago Island Company, by which the schooner Winefred is partly owned, has 70 labourers to return home. But although the company’s own schooner is lying in port and ready for sea, the men may not go by her. They must perforce be sent by the Lord of the Isles at a high rate, because the department has chartered the vessel.”

After a thorough overhaul, William at the helm of the ‘Winefred’ departed Suva on 18 September 1886 for the New Hebrides and Solomon Islands with 93 returns and a licence to recruit a full complement. She returned to port three months later (21 December 1886) with 51 recruits.

For those involved in the labour trade 1886 was quite a disjointed year with the ‘Glencairn’ not heard of again after returning 75 time-expired labourers to the New Hebrides; the ‘Christine’ back from a thorough overall in Auckland, setting off in mid-April for the New Hebrides with 122 returns and a licence to recruit 44, not anchoring in Suva harbour until early December due, in part to the Captain and the crew having been laid up with fever; the ‘Meg Merrilies subjected to a major refit, including new rigging and sails mid-season in Sydney; the return of the ‘Lord of the Isles’, also mid-season and the ‘Albatross’, after one voyage, being sold at auction for £105 following a dispute between the Captain and some of his crew over unpaid wages. Only the ‘Elizabeth’ successfully managed three voyages to return (New Hebrides and the Line Islands) and recruit labour (New Hebrides only.)

The following year, 1887, proved no different.

The ‘Winefred’ under Petrie’s command made three voyages in 1887 to return and recruit labour beginning in February to the New Hebrides and Solomons, repeated in July and with New Britain included on the December sailing, which sadly would turn out to be William’s last.

During the year, according to family sources, the Petrie family moved to Suva, but I have been unable to determine when that took place. Perhaps they travelled on the ‘Winefred’ or ‘Eastward Ho’ and were not recorded on any passenger manifests. It was also possible that the family chose not to disrupt daughter Dora’s final year of school as she did not travel to Suva until February 1888.

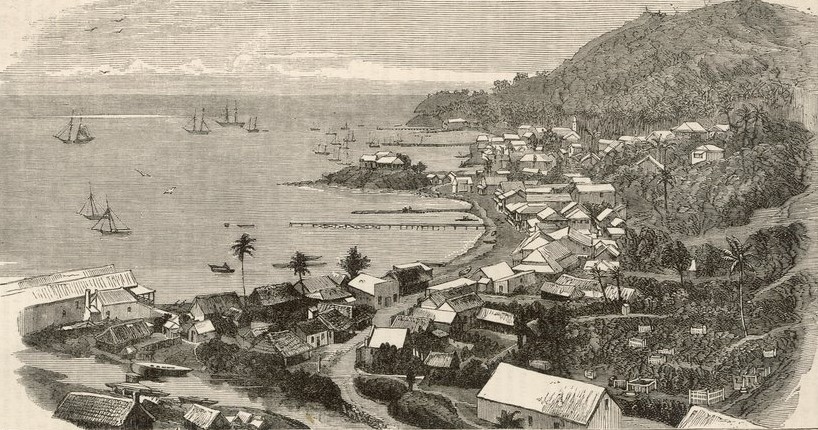

Suva Harbour (Source: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1464-ABL271-083)

As to the fate of other vessels in the trade, the ‘Christine’ which sailed in late December 1886 for New Britain failed to return to Suva with Mr Bevan the Government Agent transferred to the ‘Meg Merrilies’ for the passage home; the ‘Lord of the Isles’ departed port late January and having discharged time-expired labourers in the Solomons and New Britain opted to return to Sydney; the smaller 39 ton schooner ‘Midge’ rejoined the trade in May and for both the ‘Elizabeth’ and ‘Meg Merrilies’ it was pretty much business as usual. Indeed, the Fiji Times complimented the Master and crew of the ‘Elizabeth’ for having undertaken five voyages in a twelve month period. She too left the trade around October.

Both Meredith and Petrie again gave detailed accounts of their most recent voyages, which appeared in the Fiji Times on 24 September 1887 and 2 November respectively. I do not intend to repeat William’s report here except to capture the salient points below of an editorial (pro labour trade) piece in the Fiji Times of 2 November 1887, after having read that Petrie was one over complement, a stowaway who wished to return to his previous employer.

“Somehow it really does appear as though those who have written so pathetically on the miseries enjoyed by Polynesian (sic) labourers at the hands of their stern and ruthless masters, must have been a little misled. Their jeremiads (mournful complaints or lamentations) are not alone groundless, but everyday experience shown by the conduct of the Polynesian (sic) themselves that there never was any real foundation for them. The Legree (Simon Legree, a fictional character portrayed by novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe as a cruel and abusive owner of slaves) of Fiji appears to exist rather in the vivid imagination of its detractors than among the colonists themselves. Not that that matters much; a good story loses nothing from the trifling fact that there is no foundation for it.”

William is next reported, by Captain Fielding of the ‘Taupo’, as having left Vila Harbour, Sandwich, New Hebrides for Suva on Saturday 24 March 1888 with a full complement of Polynesian (sic) recruits. We learn further from the Fiji Times that on arrival in port on 1 April 1888 “Captain Petrie was invalided immediately on reaching shore, having unfortunately contracted fever during the return voyage. We hope to see the genial face of Captain Petrie again in a few days.” In the absence of William’s usual report, the Fiji Times, in their 4 April 1888 edition, provided an account (possibly provided by the Government Agent, Pilkington) of what was another eventful voyage. “Whilst anchored on the Western side of Pentecost Petrie and his crew witnessed the sudden eruption of a volcano on neighbouring Ambryn lighting up the whole island. Twenty four hours after the eruption lightning flashed vividly and continuously over the crater, heavy peals of thunder forming an accompaniment and so adding to the dreadful splendour of the scene.” We also learn that it was at Pentecost that William went to the rescue of a Mr Walker and his crew who were under siege by some of the local inhabitants. Tragically he was too late to save Mr Walker and one of his crew. They did however recover their bodies and return them, on the abandoned schooner, to Mallicolo. Three other Malllicolo men, forming the balance of the crew, were presumed have drowned due to wounds sustained in the attack.

According to family sources William was invited by his friend James Borron to Mago Island to recuperate, but this only made him worse, and his return to Suva was confirmed by the Fiji Times of 16 May 1888. “We regret to announce that Captain Petrie is again prostrated with illness of the same character he suffered some time back and has been brought on to Suva from Mago per Eastward Ho.”

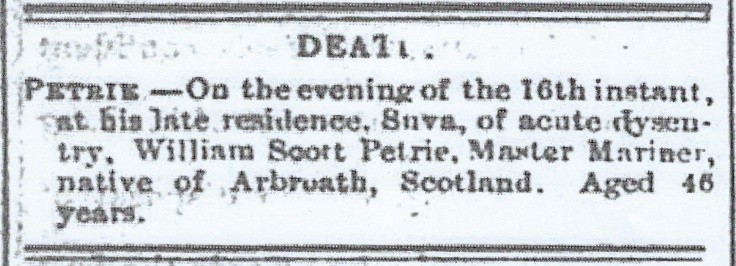

William died in Suva on the evening of 16 May 1888 from ‘enteritis’ according to his death certificate – something that is borne out by various family stories (and his death notice) of how he had been suffering from acute dysentery.

William’s obituary in the Fiji Times of 19 May 1888 read, “The illness of Captain Petrie terminated fatally on Wednesday night at about ten o’clock, when the unfortunate gentleman passed away. The funeral took place on Thursday at 11:00am, when the remains of this deservedly esteemed citizen were consigned to the grave amidst the regret of all who knew him. Eight boats conveyed the mourners, to the number of about forty, and this would have been materially increased had the hour of the ceremony been fixed for a later period of the day. As it was, many persons knew nothing of the sad occurrence until they arrived in town on the morning of the funeral, when the flags at half-mast induced enquiry and the time at disposal was found insufficient to permit arrangements being made for a more numerous attendance. In the boats were the following masters in the merchant service – Captains Calder, Meredith, Gibb, Harrison, Jones, Hedstrom, Cocks and Callaghan, while the representatives of the leading commercial house also followed. The service at the grave was read by the Reverend William Gardiner and was followed by the ritual of the Odd Fellows, conducted by Mr Robert Moss, some ten or twelve members of that Society attending in regalia. A very genuine feeling of regret is experienced at the sad fate of Captain Petrie whose unassuming character and sterling qualities had raised up for him a host of admirers and well-wishers. He was a true man; and more cannot be said. The sympathies of the community are with his bereaved widow and daughters, whose affliction at this unexpected calamity can be imagined. Time, which tries all will no doubt bring healing on its wings. One of the marked features of the funeral was the spontaneous attendance of a number of Polynesians (sic), some of whom claimed the right to pull the boat containing the coffin, on the ground that they had once belonged to the boat’s crew of the deceased and ‘he was their white man.’”

Captain William Scott Petrie was buried in Plot number 567 in Suva Cemetery. His headstone was destroyed by the earthquake of 1953, and I am told was pieced together by my Grandmother Minnie Abrahams. John Thomson was able to take down the inscription on a visit in 1981. See below:

The fractured headstone has since disappeared, and as soon as the location of the plot is confirmed, we hope to replace it with a new one.

William left his property, valued at £781, 2s and 7p, to his wife, Emma.

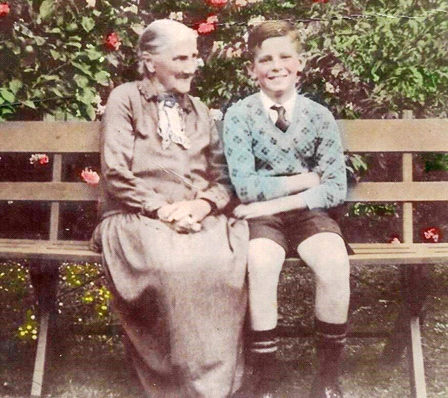

William’s eldest daughter Maud was nineteen at the time of his death and it is reasonable to assume that she had already met her future husband Herbert, possibly through the Mago Island connection or in Levuka. They married in 1892 and had five children including John’s Grandmother Constance Penelope (Connie) and my Grandmother Maud Wilhelmina (Minnie) Ambler.

The children’s mother died six days after giving birth to Minnie. She was followed three months later, and rather suddenly, by her two-year-old daughter Joyce who died of ‘convulsions.’ Herbert, along with William’s wife Emma and others, took responsibility for raising the four remaining children, which included bothers Lloyd and Victor. This responsibility fell increasingly to Emma, Connie and their Aunt Dora Ragg (nee Petrie) after the death of Herbert in 1908. Emma, or Granny Petrie as she was known, moved to Auckland in 1921 where she lived with her younger daughter Florence (Florrie) and granddaughter Dorrie. She died on 12 January 1937 aged 91 and is buried in Purewa Cemetery.

The family line continued in Fiji for another four, in some cases five, generations with Connie marrying William (Bill) Kearsley (telegraph and wireless engineer); Dora and Hugh Ragg (considered by many the father of Fiji’s tourist industry); Florrie and Robert Boyd OBE (Chairman Native Land Commission and member of the Legislative Council) and my grandparents Minnie and Vivian Abrahams (see separate entries on this website.)

I add, as a footnote, that Petrie’s last command, the ‘Winefred’, was offered for sale or charter in the Fiji Times of 9 June 1888, where it was stated that, “The success of this vessel in the Polynesian Immigration Service is well-known and undoubted. Liberal terms and reasonable assistance to an approved buyer.” In a subsequent advertisement the asking price was set at £700. I should also draw attention to the demise of the Mago Island Company for which both our 2x Great-Grandfather William and Great-Grandfather Herbert worked. The company, registered in the Colony of Victoria, was forced into liquidation on 22 September 1888 as the owners were unable to repay loans secured from Fraser and Company of Melbourne, with all property, both real and personal, belonging to the Mago Island Company passing to the mortgagee. This would have included the ‘Eastward Ho’ and Mago’s share in the ‘Winefred.’ The ‘Winefred’ (purchased by Captain Hans Christian Hansen Kaad, master mariner, island trader and copra merchant) was blown ashore in heavy winds on 15 February 1892 whilst unloading cargo and shipwrecked at Oniafa in Rotuma. The ‘Eastward Ho’, acquired by John Robertson of the Navua Trading Company, slipped out of Suva Harbour sometime after July 1892 and was not heard of again until a report surfaced of an alleged attack on its crew by locals at Nonouti in the Gilbert Islands later that year. Some four years later, after having been sold to Mr G Krafft, she ran aground, with a cargo of timber, some ten miles from Udu Point. The success or otherwise of attempts to refloat her remain a mystery. I also found it interesting that a writer for the Fiji Times (13 October 1888) appeared to have been surprised by James Borron’s premature departure from Mago and unaware that it was his apparent mismanagement of the business that brought about “recent changes in the position of the Mago Island Company.” The sugar mill was dismantled in 1895 and used to expand Penang’s capacity. Both my maternal Grandfather, Les Sherwood (see separate article on this website), and my father were future Managers of CSR’s Penang Mill (alas no longer operational due to the massive and irreparable damage sustained in the wake of tropical cyclone Winston in February 2016.) Given the family connections with Mago, my wife and I were delighted to have spent some time on the island in 2017.

The Landing Place Mago Island, June – July 1884 (Source: Burton Brothers Studio, Dunedin. Alfred Burton. Purchased 1943. Te Papa Museum of New Zealand)

In conclusion, I recount a recent voyage on Cunard’s Queen Elizabeth, where I noted that the Deputy Captain of the vessel was a Lindsay Petrie which of course, as a direct descendant of another Captain Petrie, made me wonder whether we were related? It so happened that Captain Petrie announced, in what I was told was a typical Edinburgh brogue, that he was at the helm for our departure from Tokyo, which made me even more curious as our Petrie ancestors all came from Fife. My first attempt to meet Captain Petrie failed, but I persisted, much to the chagrin of my wife and sister, and you can imagine my excitement when I did receive a call and an invitation to drinks from the Deputy Captain. Alas, he told us that he was not aware of any seafarers in his family line though he lived some 20 minutes from our ancestral home! Not deterred I advised all the Petrie relatives of Fiji descent of this chance encounter, and I did warn Captain Petrie that he would find his way into our family history. He is now known by all as ‘Cousin Lindsay!’

I am indebted to my bona fide cousins John Thomson and Virginia Nicholls, both of whom have thoroughly researched the various branches of our family, including the Petries. John’s histories were a most valuable resource for me, and I am grateful for his permission to use some of that information here. My thanks also to Lindsey Shaw of the Australian National Maritime Museum, Sydney for providing important background material on some of the vessels and crews mentioned in this article. Likewise, what appears to be the only known photos of Captains Petrie and Meredith were in the possession of my Grandmother Maud (Minnie) Abrahams nee Ambler, and for this I am also grateful.

We (John, Virginia and I) are three of the many 2x great grandchildren of William Scott and Emma Mary Petrie.

1882 Map of The Fiji Islands (Source: The ‘Australian Handbook’ Gordon and Gotch)