By Robyn Mortimer

WW2. The islands of Fiji are in the midst of the Pacific theatre of war. These were worrying times for my Grandmother Maggie Brown Parker resident in Sydney with her family while half-sister Lulu Marlow and McGowan brothers William, Gordon and Andrew had their homes in the Fiji Islands. News from Fiji was scarce. Then at last with Peace and the end of hostilities normal shipping in the Pacific recommenced and Andy McGowan, her younger brother by two years wasted no time sending his sister Maggie the fare for her passage home.

BULA MAI VITI- WELCOME HOME TO FIJI

McGowan and half-sister Lulu Marlow, her nephews and nieces. She is fortunate to obtain a berth on one of the Matson Liners carrying young Australian war brides to America to join the Yankee sailors, soldiers or airmen they had fallen in love with and married during the war years.

I have vivid memories of this time in my life. It is 1946/47, by now I am a very young boarder at a convent in a Brisbane bayside suburb, eagerly awaiting the return of my beloved Gran. Our reunion revolves around small Kodak box brownie photos and gifts to excite an eight-year-old; lustrous seashells, exquisite silk handkerchiefs I understood must never be used for the nose blowing job. Only six of those miniature snaps have survived the years, enough to give me a glimpse of a happy Maggie surrounded by tanned brothers in their Sunday best tropical gear, of posed shots with grown-up nieces, a dockside greeting, or was it a departure, a view of a ship but not its name, and brief backgrounds of a tropical island. Not nearly enough to satisfy the latent curiosity of a grown up me.

The brothers, Andy, Wink, and Gordon made sure Maggie covered every tiny part of Fiji, both the Levuka Island haunts of her childhood and the surprising new ventures of a modern island nation, the sugar mills of Lautoka, the gold mines at Tavua, the acre upon acre of rice fields and plantations.

When later asked by newspaper reporters the highlights of her visit home, she spoke of the outstanding change to the education of Fiji’s native youngsters, the schools where children both native and white sat side by side, their lessons delivered in the English language. The equal opportunity to attend New Zealand universities.

I doubt any of the Fiji born McGowan offspring knew a great deal about their parent’s history, Geraldine Sweeny the girl from Sussex and William McGowan the sailor from Scotland. The few times I remember asking Gran about her mother’s origin the replies were vague. She was a schoolteacher from Wales, was one story, her father’s family were lawyers in Scotland another. But Gran never seemed sure of these facts, they seemed quite jumbled.

Later as I asked the same questions of cousins and aunts and even later of newly found McGowan kin from those Fiji families, the stories became even wilder. William, the Scots grandfather for instance became a James and even a Robert, the meeting and courtship of Maggie’s parents taking place in Scotland, in England or on a boat. The McGowan great grandfather traded in sandalwood, on one hand owned the boat or didn’t, died at sea or fell down the stairs at home.

But at that same time, back in the 1870’s, while Geraldine and her sea-going husband William McGowan were living in the tiny town of Levuka, Geraldine’s parents and siblings back in England were going through their own personal heartbreak and disaster. One of Geraldine’s London based sibling offspring, a young nephew, in this particular post- war timeframe, will have an incredible effect on both me and on Maggie.

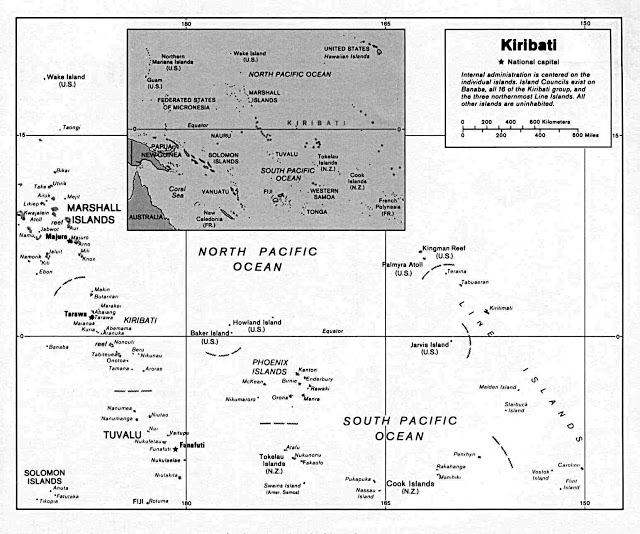

A CURIOUS CONNECTION WITH AMELIA EARHART & NOEL COWARD

Canton Island is just one of numerous small atolls in the Gilbert Ellice Islands region of the Pacific now known as Kiribati. Part of the Phoenix group close to the equator, the islands low rainfall though had always prevented colonisation. For a time, the only visitors to the small sand cay were whaling and guano ships. In the 1850’s Britain made an initial claim to the island group, reasserting sovereignty in 1936 when the islands came under the jurisdiction of His Excellency the High Commissioner for the Western Pacific at Suva, Fiji.

Then in 1937 the island was visited briefly by New Zealand and American scientists witnessing a total solar eclipse under the auspices of the National Geographic Society. At this time the American party, which included a number of Chamorro labourers from Hawaii, claimed the island for the United States erecting a small monument with two American flags.

Frank Fleming, no doubt representing the British High Commission, is the balding man in white immediately below the word ‘Canton’. Woman to the left of photo wearing a hat and dressed in fashionable slacks more than likely suitable for climbing in and out of government watercraft is not named but assumed to be Lucy Fleming.

Canton Island became a bone of contention with both countries operating manned bases on the tiny sand cay almost side by side: The British with their three radio men each day raising and lowering the Union Jack and the seven-man American group doing the same with their Star-Spangled Banner. The stand-off wouldn’t be resolved until 1939 when London and Washington signed a joint administration agreement to control the Canton and Enderbury Islands condominium for the next forty years. America however, recognizing the strategic value of Canton Island’s sheltered lagoon quickly established a Pan Am Airlines base for their Honolulu to Auckland flying boat clipper service. This included luxury hotel accommodation for passengers should an aircraft be forced to stay overnight.

A house built from packing cases (as described by a NZ newspaper) is eventually built beside the crude British shacks and Lucy joins Frank on the island where he has spent the past year alone with only a Gilbert Islander and his family as helpers, maintaining the island as a radio and weather base for Britain. Supplies and equipment are transported from Fiji by navy boats and passing ships. By this time there is a great deal of low-key spying and counter spying going on with close tabs being kept on Japanese movements in the Pacific.

Frank Fleming and two others manned the British radio communication shack, essentially a radio base and weather station virtually next door to the Americans. As Noel Coward would later so aptly put it, the Flemings in their ‘packing case’ home were entitled to display ‘a certain irritation at the Americans who have so much luxury.’ On the island their co-existence, Pan Am staff and the Flemings, is friendly; in the high echelons of politics though, relations remain guarded and frosty. Lucy lived with Frank on the island until war news from Europe indicated the conflict might reach to the Pacific. She then returned to Fiji.

In the years between 1937 and 1941 Noel Coward and Amelia Earhart would both have a fleeting influence on the Flemings lives. The second person they would never meet, the first though would become a life-long friend.

By coincidence Frank happened to be working in the general vicinity at the same time where and when it was thought the American pilot so famously disappeared though his name wouldn’t be associated with Earhart until 2003. But it was in the immediate years following her plane crash, and influenced by Japan’s increased interest in the Pacific region, that the United States establishes a Pan Am flying boat base on Canton Island.

Pan Am used the base as a halfway point between New Zealand and Hawaii, building a luxury hotel for staff and passengers should aircraft need to make emergency landings. The dual use of the island continued until the start of the war, with the Americans ostensibly running a commercial venture on one part of the island, and the British maintaining their own radio communications system on another. It worked very well, even though the British transmitted much of their communiqués in code, maintaining a political secrecy.

Actor and playwright, Noel Coward was a man of many faces, an accomplished writer, stage and film performer and unofficial British envoy, he was also a delightful house guest. On a trip from Australia to Hawaii just before war in the Pacific was declared, he stayed for a month between flights at the Pan Am hotel on Canton Island. During this visit Noel established a rapport with Lucy and Frank, beginning a friendship that would continue until Frank’s death in 1968.

Noel Coward would later write in his book ‘Future Indefinite’…

’The official British residents were a Mr and Mrs Fleming. Frank Fleming had built the house, aided by some Chamarro boys, virtually with his own hands. He ran the radio office, raised the Union Jack solemnly every morning and lowered it every night. They were two very nice people. I called on them after dinner and had drinks with them. Both typically English in the best possible sense, simple, unpretentious and getting on with the job.

They came here alone, before Pan America, from Fiji. He built the house they live in and she joined him later. They have relatives in London and Sussex and suffer occasionally from bad bouts of homesickness coupled with a certain irritation at the Americans who have so much luxury.’

Coward and Lucy may even have shared mutual friends. Bernard, Frank’s brother, had been a variety artist and stage manager for one of London’s major theatres at a time when Coward himself was an aspiring young actor and performer.

Frank remained on Canton until 1942 when sick and exhausted he was evacuated to Suva where he finished the war as an official wartime censor. Noel Coward kept in touch, arranging, as Frank had requested, a Royal photograph to be forwarded from the Queen. Coward even wrote a story loosely based on the Flemings that he called Mr and Mrs Edgehill, later made into a film starring the British actress Judy Dench.

Frank would have been aware at the time, of the mystery surrounding Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan’s disappearance. Not only had Cousin Frank been involved with initial planning of the Canton Island base, he had also spent some time in an official capacity as assistant Commissioner on other islands in the Gilbert group. Following the bombing of American bases in Hawaii, the American High Command took over Canton Island, Pan Am services ceased and the Pacific very quickly became a major theatre of war.

But while WW2 overshadowed the mystery disappearance of Amelia Earhart’s aircraft, the circumstances surrounding the crash never disappeared from public view. Over the years, countless sightings of either the aircraft or pieces of wreckage were duly reported and discounted. As recently even as March 2011 newspapers carried news of the sighting of a submerged aircraft suspected to be Earhart’s Lockheed in waters off New Guinea.

It is however a 2003 report of a sextant box in Fiji that sets in motion yet another flurry of interest…so far as this story is concerned a very important and fortuitous one.

The search for Earhart’s plane and the controversy over her death had continued on and off for many years, until the Fiji discovery came to the attention of the International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery, known as TIGHAR, which then sent two men to Fiji to investigate this latest claim. They were on an official quest to investigate the recent finding of a sextant box thought to belong to Amelia Earhart and her co-pilot, Fred Noonan.

Martin Molenski, a Jesuit priest from Buffalo and Roger Kelley ex-Marine sergeant formerly with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s office duly located the box in question in the home of Dr Gerald Dennis Murphy. The box had come into the doctor’s possession when a patient and friend, Frank Fleming, lay dying in a Suva hospital. Doctor Murphy himself was now ill, his mind was failing, and he was virtually on his deathbed.

A Catholic priest and close friend, Father Michael Bransfield arranged for the TIGHAR team to search personal effects in the doctor’s home. They found the reported box, but it was obviously not the box they were searching for. Then Father Bransfield reminded the housekeeper about another box that the doctor and his wife would often bring out at dinner parties to show their guests.

The housekeeper fetched a small copper container, green with age. As Martin Molenski said, it was a treasure chest, just not the one they had travelled halfway round the world to find. And yet its contents were so intriguing, instead of walking away the two men from TIGHAR delved further.

As Molenski and Kelly soon discovered the box held the mementoes of Francis Ivor Fleming, a friend and patient of Dr Murphy who had given the box to him in 1968 just before he died of tuberculosis in a Suva sanatorium.

Inside the box was Frank’s birth certificate, his appointment as a World War 1 Lieutenant in the Royal Flying Corps, first day issue stamps, signatures from early aviators, letters from his sister in England, flags he had flown over Canton Island, newspaper clippings, five handwritten poems by Noel Coward, Frank’s deathbed diary and five rolls of damaged photographs and film.

Dr Murphy died not long after the TIGHAR visit and the box and its contents passed into the care of his daughter Denise Murphy. The spools of film, by now sixty or more years old, were in a sad condition. Roger Kelley hoped they could be salvaged and restored by the American College of Forensic Examiners. Denise relinquished any hold on the sixty-nine-year old spools of film to the Americans and thus began the long and arduous process of converting approximately 200 negatives to digital format. The task was completed in 2007, and the negatives were promptly placed on Photek’s website for viewing and discussion.

In the meantime, Frank Fleming’s modern-day kin back in England had no idea all this was taking place. Nor did I.

FRANK’S LEGACY

While the lengthy TIGHAR and PHOTEK investigation was being completed, the adult me was becoming thoroughly immersed in the slowly surfacing story of Frank Fleming’s incredible life, together with the discovery of newly found British kin. Even though there were letters from Frank’s sister in England among the contents of the box these were not part of the American search. Nor for that matter had they been closely perused by either Dr Murphy or his daughter in the 35 years following Frank’s death. For my newly found Fleming cousins, the emergence of Frank’s life story was incredibly precious, but at this stage I was still unaware of the impact it would have on me.

The Americans had taken possession of the five rolls of film from Frank’s box, they were after all in bad condition and in dire need of expert assessment, but the rest of the boxes content remained with Dr Murphy’s daughter Denise, who by then was living and working in Hong Kong. Mention had been made of a death bed diary among the boxes contents which naturally the Fleming ‘cousins’ in England were keen to read.

The American College of Forensic Examiners had their work cut out attempting to restore and convert to digital image the more than 200 negatives from Frank’s rolls of film; some were colour 35mm, some half frame, some from a Leica camera. All were affected by age and tropical heat. The resulting photos were scanned by Jeff Glickman and Photek with the images generously made available for public viewing on Photek’s secondary website. It was mid 2007 by the time I came across this website collection of photos after being alerted by the Flemings in England. They had looked through the footage but apart from what were obviously shots taken of Canton Island, without at that stage the diary, they were really none the wiser in regard to names and places.

I’m a night owl, happiest researching and typing in the quiet early hours before dawn. I was curious to see photographs taken all those years ago by Geraldine’s nephew. I imagined they would be photos of he and Lucy, and probably of their years on Canton Island. So, I approached the five film sets with nothing more than curiosity. Roll A was, as I thought, still camera shots of everyday life on Canton Island circa 1940, fascinating, nevertheless.

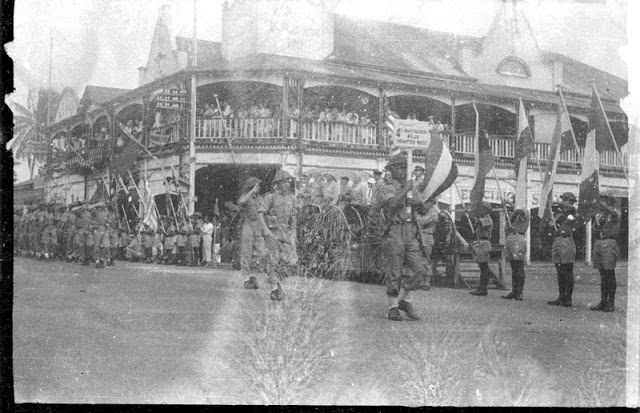

The next spool showed what was obviously a victory march through Suva that could be dated to 1945. Then an extremely damaged shot of Lucy shown strolling with friends on an island. This would have predated the 1945 film and could have been taken as early as 1937, most probably on Laucala island.

The next and last photo of Lucy is taken on a launch taking her the fifteen kilometres from Nukulau to Suva, or perhaps making the reverse trip home. Lucy has aged, no longer the eager young woman revelling in her first taste of the islands; but we must remember by now she would be in her late seventies. She has potted some of her precious plants, a gift for a friend, for Lorna McGowan perhaps, Andrew McGowan’s daughter, or maybe even Frank’s cousin Lulu Marlow, Geraldine’s Foreman daughter. Her dress is the same simple style that suits her so well, her face is framed by a shady hat, she wears small stud earrings and just a faint dash of lipstick, a pale pink.

By some strange quirk I had chosen to view the second roll last. Nothing could have prepared me for the images I was about to see. This was movie film, described as extremely brittle, with 50% of the negatives fused and impossible to separate. The quality of the salvaged stills was bad, the subject matter in most cases faded and indistinct. But there was enough detail and clarity for me to recognize two of the three women pictured greeting each other, laughing and smiling as they strolled through a tropical garden.

For an astonishing moment time stood still: I didn’t dare believe the images on the screen. I sat there, alone at my computer, bringing up each sequence. It was the fourth image that set my skin tingling, brought a quick rush of tears. I was immediately carried back more than sixty years to my childhood.

The woman I was looking at on that resurrected film clip, exactly as I remembered her, was my much-loved grandmother Madge Maud Brown Parker, nee McGowan, born 1877 in Levuka, married 1900 in Levuka to Charles Brown Parker, Indiana born. Tears threatened, unprepared for this unbelievable surprise. I could only gaze in disbelief. Sitting in my Brisbane home, sixty-five years after this photographic event and many, many miles distant, watching my Maggie, in Fiji, strolling through a garden with her sister in law, brother Gordon McGowan’s wife, Minnie Rosa. The slim younger woman with them had to be the photographer’s wife, Lucy.

I owe Frank Fleming my heartfelt thanks. In filming Lucy and his cousins, Minnie McGowan and Maggie, he was creating an incredible gift, one that wouldn’t reach its unsuspecting recipient for sixty odd years; the gift for me was, of course, my darling Maggie’s smile.

Special thanks for this story must be given to by the American College of Forensic Examiners, Jeff Glickman and Photek, Father Martin Molenski and Roger Kelly from TIGHAR, Dr Murphy and Denise Murphy, and again the input of the modern day English Flemings father and son, Peter and Kim who each in their individual way maintained a vigil over Frank Flemings life and times.

Without all these wonderful people I might never have enjoyed that last glimpse of my Grandmother, Maggie.