PARHAM, WILFRID LAURIER

PARHAM, WILFRID LAURIER

(March 18, 1900 — November 13, 1942)

Agricultural Officer,

Dept of Agriculture, Fiji 1930-1942

2nd Lieutenant, Platoon Commander, Tailevu Company, Home Guard

Commended for Introduction of Irrigation in the Central Division, Viti Levu

By Phyllis Parham Reeve

![]()

My father began keeping a journal in 1912. He was the same age as the century, and for him the most significant event of the year was the sinking of the Titanic. The pages are heavy with paste and newspaper clippings. Most other entries concern the weather, which on the west coast of New Zealand was usually either wet or not. That journal was a beginning.

He continued to write, and although I imagine he would be surprised to know it, his writings, with accompanying photographs, are the legacy which he left me to share. Besides the journals, personal and official, he wrote letters, magazine articles, scientific papers, stories and poems: a detailed documentation of a life and time.

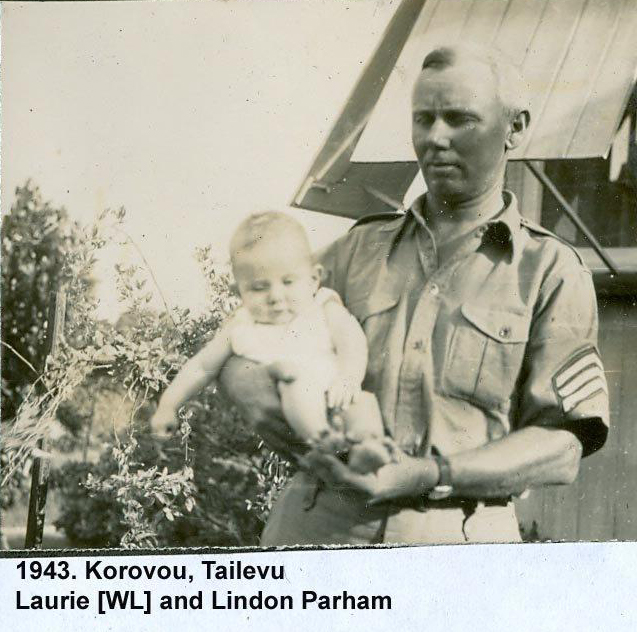

Named by his Canadian father in honour of the prime minister, he disliked the name “Wilfrid”. My mother called him “Laurier” or “Laurie” and that is the name by which I think of him. He died suddenly before I was five, so my memories of him would be few, had not my mother continued our conversations and family customs, looking at photo albums and identifying people, places and occasions so that even my little brother, 3 years my junior, believed he remembered them. She kept the thirty years of diaries, which in the fullness of time came to me to complete our interrupted acquaintance.

Laurier’s parents, Charles and Richenda Parham, left South Africa for Hokitika, New Zealand in 1907, with their children, Charlie, Laurier, Bayard, Beatrice and Helena.

Journals from his teen years show a boy at his books, especially history and classics, but also foraging in the bush and along the shore. He drove himself physically, then and later subjecting his slight frame to the motto “Mens sana in corpore sano”.

He began studies at Canterbury College in Christchurch, but an accident during cadet training damaged an eye and put an abrupt end to both his academic and military aspirations. The journals became more substantive as his childhood curiosity developed into an insatiable interest in people, from nurse’s aide and sergeant-major to farmhands, miners bank managers and schoolboys, wherever his various jobs took him. He needed to know how things worked, made careful notes, and seldom forgot what he learned.

Laurier’s father leased a plantation in Fiji as a postwar rehabilitation project for the eldest son Charlie, who had been struck by a severe infection while in England training for deployment and was detained in hospital for more than a year after the Armistice. Ironically, Charlie spent very little time in Fiji, while the rest of the family made the islands their home and life’s work. The mother Richenda [H.B.R. Parham] became a respected authority on native plants, their names, descriptions and traditional uses, as well as on local and pre-cession history.

In 1921 Laurier arrived at Rukuruku Bay in Bua, Vanua Levu

As his father’s health deteriorated and Bayard was often away at college, he found himself by default leading the day-to-day labour on the plantation. He was very young, and learning as he went, not only how to grow coconuts, hunt wild pigs, and nurture livestock in a venue very different from a New Zealand farm, but also how to interact with the people who were there before him.

The European community along the coast was small: a few settlers, sailors bringing supplies, and itinerant officials, some more helpful than others. He needed to hire and trade with the Fiji people in the neighbouring villages, and here more than anywhere he had to trust to trial and error to pick up important procedures and protocols, as well as the language, which he and indeed the whole family learned surprisingly quickly.

The journals are full of details of planting and harvesting, attempts and failures and breathtaking excursions along the trails or lack thereof between villages. There are also pages of notes from private studies, especially of Latin, and of his own creative writing. The poetry was much worked over and pondered but never saw publication. Some of the prose appeared in Fiji, New Zealand and British papers, at first fiction of the Boy’s Own genre but maturing to semi-documentary stories based on local history and folklore, for instance a rousing account of Charlie Savage’s battle at the Seseleka, and a tale involving the serpent god Dakuwaqa. Truth was indeed stranger than fiction and what he heard more wonderful than anything he could imagine.

After his father’s death in 1926 Laurier knew he had neither the physical nor the financial resources to continue the plantation. He found employment with Pacific Timbers Ltd at Dreketi as” most likely storekeeper, possibly teacher and surveyor, occasionally carpenter, certainly interpreter and always available for sudden needs.” From time to time he rode on horseback to check on the plantation, and in 1929 returned for one last attempt. He was studying and documenting the land as he worked. He introduced himself to the Department of Agriculture by submitting a 15-page paper “Ecology of the Coconut in Navakasiga” together with a list of Vanua Levu plant names, and in 1930 began his career in earnest.

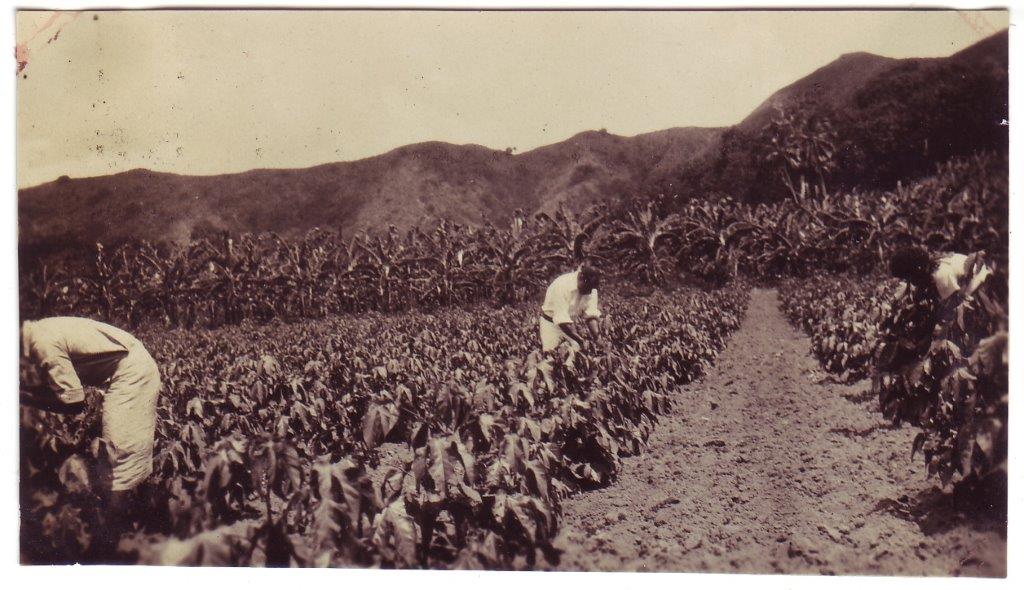

The Agricultural Station at Sigatoka in Central Viti Levu

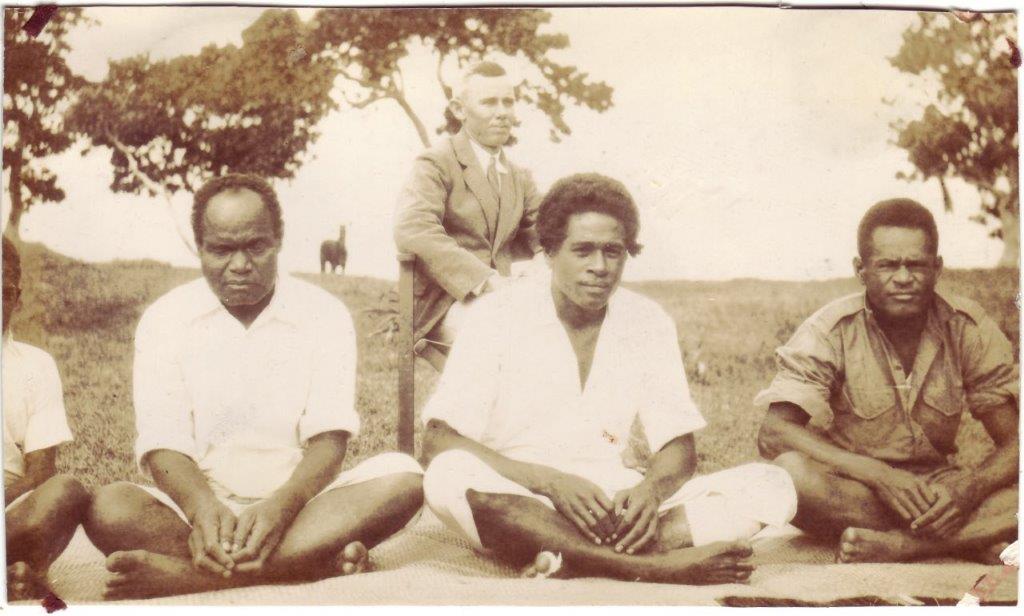

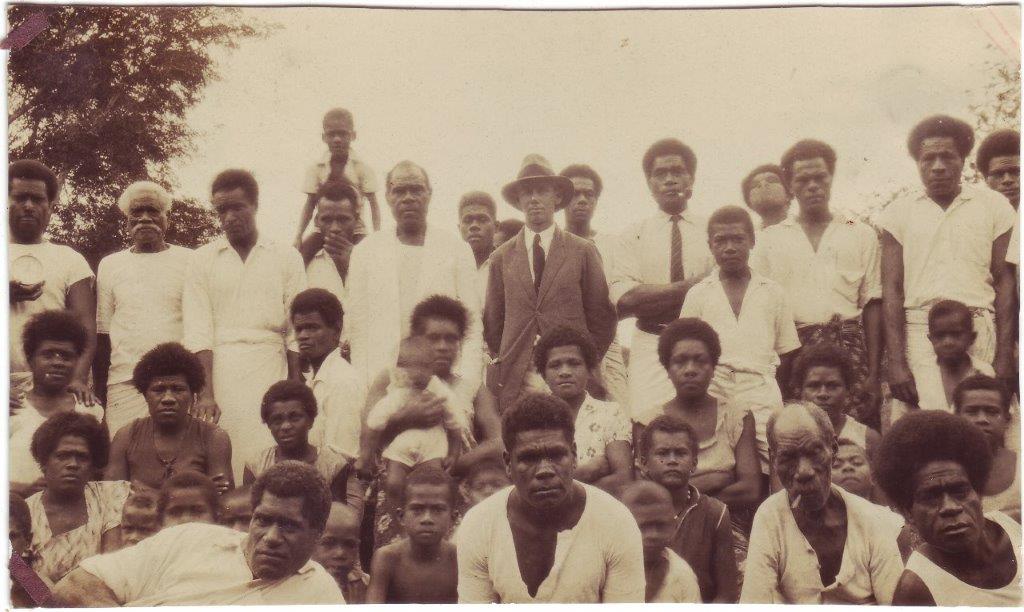

The agricultural station at Sigatoka in central Viti Levu was embarking on a programme of education which trained “Native assistants” in methods to implement in their own villages under supervision of Laurier and his colleagues, headed by R.R. Anson. Soon he was part of a society which embraced not only the Department of Agriculture employees, but also those of the Colonial Sugar Refining Company and even the Roman Catholic mission, as well as the villagers. There was time for much work, which he loved, but also for study and play. He learned to play tennis and to speak Fiji Hindi.

For the next five years he devoted his entire being to the programme and the people, travelling on horseback far up the valley and into the hills, spending far more time in the villages than at the Station and carrying a camera. He kept two parallel journals, the continuation of his private autobiography and the formal civil service diary in which he recorded details of personnel and their work. These complement each other and in the book I compiled on Laurier’s behalf blend into a single narrative. [The diaries are in the microfilm collection at Pacific Manuscripts Bureau.]

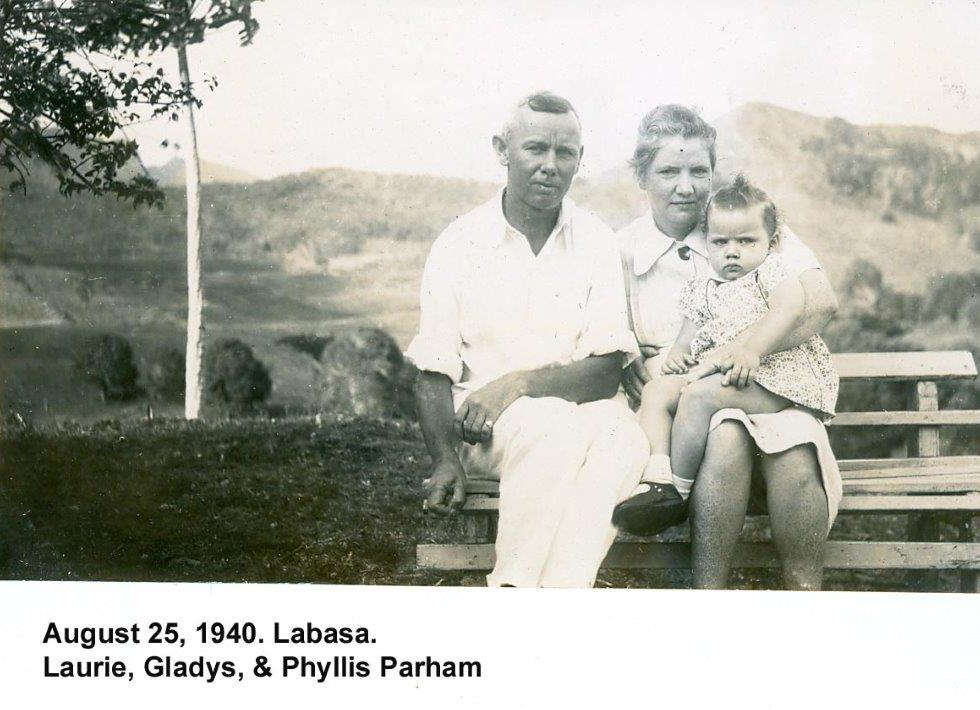

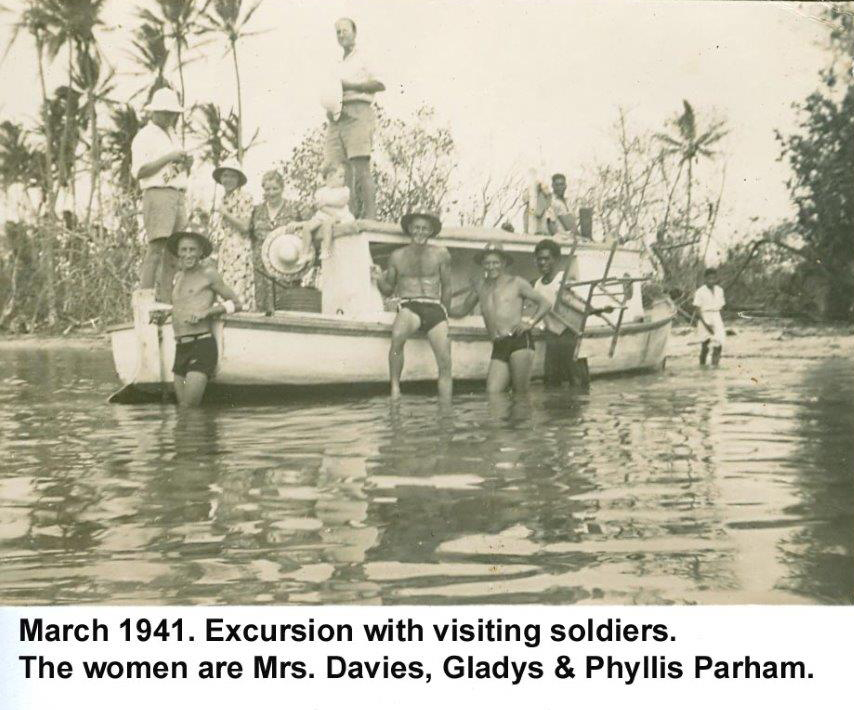

In 1935 he went to Britain on leave, and travelled via Canada to meet his father’s family in British Columbia and Quebec. Stopping in Montreal, he met his second cousin Gladys. The personal journals stopped, and my history began. On his return to Fiji, Laurier was appointed to the Station at Dobuilevu near Korovou, Tailevu. Again his work involved travels far into the interior of Viti Levu but from a different direction. Again he worked closely with the Native Assistants. After many letters, Gladys joined him and they were married in Suva in March, 1937.

In 1935 he went to Britain on leave, and travelled via Canada to meet his father’s family in British Columbia and Quebec. Stopping in Montreal, he met his second cousin Gladys. The personal journals stopped, and my history began. On his return to Fiji, Laurier was appointed to the Station at Dobuilevu near Korovou, Tailevu. Again his work involved travels far into the interior of Viti Levu but from a different direction. Again he worked closely with the Native Assistants. After many letters, Gladys joined him and they were married in Suva in March, 1937.

I was born in July 1938. A few weeks after my first birthday we travelled to Canada and were in Montreal at the outbreak of war. I think Laurier had it in mind to leave us safely with Gladys’s family while he joined the Canadian Army to fight for what was still the British Empire. The plan had numerous problems and contradictions, not least his growing impatience with imperial bureaucracy blundering into colonial affairs. His superiors at the Department of Agriculture refused permission for him to enlist, claiming correctly that he could more effectively contribute to the war effort by continuing his leadership in food production and building on his relationships with communities in the interiors of the larger islands.

So we returned to Fiji. After a few months at Labasa, during which he found occasion to learn the eastern half of Vanua Levu almost as well as he had learned the western in his plantation days, we were back in Tailevu. His brother Bayard was stationed at Nadruloulou and both became increasingly involved in guiding Native producers’ involvement in distribution and economics.

Commendation

In 1941 the Director of Agriculture formally commended him on the successful introduction of irrigation in his Division and his “continued efforts to secure supplies of foodstuffs for the Gold Mines and success in securing increased rice plantings, repayments on advances and improvements on the two farms” under his control.

After Pearl Harbor Laurier was commissioned as a Temporary 2nd Lieutenant while holding the appointment of Platoon Commander, Tailevu Company, Home Guard. The islands interested New Zealand and American forces because of strategic use for “rural tracks and camping sites” and even potential locations for a POW camp, so he was called upon to conduct guided tours and undertake exploratory reconnaissance visits to smaller islands.

After Pearl Harbor Laurier was commissioned as a Temporary 2nd Lieutenant while holding the appointment of Platoon Commander, Tailevu Company, Home Guard. The islands interested New Zealand and American forces because of strategic use for “rural tracks and camping sites” and even potential locations for a POW camp, so he was called upon to conduct guided tours and undertake exploratory reconnaissance visits to smaller islands.

He continued to document his work in his official diary. To publicise and promote the Demonstration farms he contributed technical reports to the Department’s journal and human interest stories with photos to the Pacific Islands Monthly and the Fiji Times. In evenings at home, he worked on what he hoped would be a published compilation of his observations of Fiji life and customs. Some of the Notebook refers to earlier written sources, but much is based on his own observations and questioning of Fiji elders and storytellers.

On ceremonial occasions he copied out the mekes and songs, including an original “Song for the Waimanu Demonstration Farm” in which the student farmers describe their work. He did not have time to finish his project, but thanks to 21st century technology, I have been able to make the Notebook in pdf format available as a resource for interested scholars.

In November 1942 Laurier died very suddenly of complications related to appendicitis. What would he have done had he lived after the War? He felt he had gone as far as he could within the Department, given his lack of formal post-secondary education. Perhaps we would have returned to Canada, maybe to rural British Columbia, where the climate resembles that of New Zealand.

In November 1942 Laurier died very suddenly of complications related to appendicitis. What would he have done had he lived after the War? He felt he had gone as far as he could within the Department, given his lack of formal post-secondary education. Perhaps we would have returned to Canada, maybe to rural British Columbia, where the climate resembles that of New Zealand.

Burua Ceremony

Before Gladys left Fiji with my baby brother and myself, she received a letter from the Dobuilevu Demonstration Farm. Written in Fijian, it was presented with an interline literal translation which may be in Bayard’s handwriting. It is the best concluding tribute…

19th November 1942

Mrs. W.L. Parham

I’saka

This letter is from us the assistants of Mr. W.L. Parham, Usaia T. Tawakeivou, Osea Kaloumaira, Rupeni Rawaqalailai and also from all the settlers at Dobuilevu to you the Lady of our Chief and our Father who has passed away suddenly in this our land of Fiji.

This is the true expression of our hearts towards you, whereby you will know with certainty that we are united as one in bearing the burden of great grief which weighs you down – owing to the passing of the Chief your husband from your presence and from ours also at the height of the performance of his duty – carried out with the love of a father in our midst and on behalf of our peoples at this time of great difficulty on account of the war.

We shall never be able to forget his work so great and valuable and useful, which he carried out here on behalf of the true Fijian race and we will not forget how he always shouldered all our heavy burdens in order to aid us.

We bear witness in your presence to the fact that the time during which you both were in charge of our affairs has been a time of the greatest value to us all.

The whole manner of his kindly works of leadership to us, and your own friendliness to use whenever we approached your home, or whenever you came to visit us in our homes will remain with us as a remembrance of you both.

There is a truly chiefly ceremony by which we always pay respect to the memory of our relatives who pass on, and we ceremony we have carried out at Dobuilevu in his memory. The name of this ceremony is the “Burua”.

This we have duly carried out.

We hope and pray that a time and happiness and prosperity awaits you and the two children when you return to your home abroad.

We pray that there you will follow you the love of God our Father to bring you happiness in the days to come.

We pray God will protect and be with you and the two children and that He will bless their days with useful and honourable service.

Ends thus our letter – with great affection to you and the two children.

From Usaia T. Tawakevou

on behalf of us all.

References:

The journals in microfilm are held by the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, Canberra.

The book On Fiji Soil; memories of an agriculturalist, based on the journals of W.L. Parham 1918-1942, Institute of Pacific Studies USP, 1989, by Phyllis Parham Reeve is partly reproduced on Google and turns up readily on book selling websites.

Additional Photographs are on my Flickr site. https://www.flickr.com/photos/pmargery/sets/

![]()

Entry By: Phyllis Parham Reeve, Gabriola, BC, Canada

mailto:phyllispreeve@gmail.com

All photographs from the collection of W.L. Parham, used with permission.