Written by Sir Charles Stinson in 1981.

![]()

My mother, Ella Josephine Griffith, who was born in Glasgow Scotland and soon after moved to Wales, came to Fiji in 1900 after the death of her parents to be adopted by Mr G. L. Griffith, her uncle, who founded the first newspaper, The Fiji Times and before Cession ran the postal services in Fiji and was a member of King Cakaubau’s Cabinet way before Fiji became a British Colony. He was also one of the founders of Suva and served as its first Mayor. Little did he know that his grandson myself would follow him. Looking at the portraits of Mayors in the City Council the physical likeness is amazing which was commented on by the Queen Mother on a visit in the late 50’s

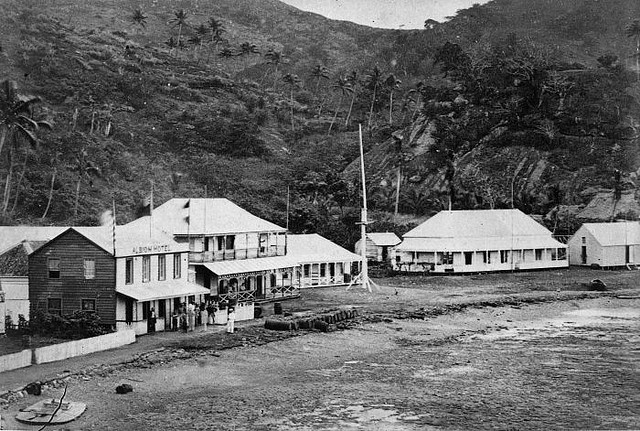

My father, John Bolton Stinson, an Irish Canadian, born in Toronto, Canada, was invited by his uncle, Archdeacon Floyd, founder of the Church of England faith in Fiji and builder of the first church, the Holy Redeemer at Levuka, to come to Fiji and arrived in 1902.

My father set up a photographic business mainly in portraiture and used as his studio a room in the Mance. He met and courted Ella Griffith and on the 19th February, 1906 they married and returned to Canada. On arrival in Canada my parents bought a property and erected on it a tent to use as a temporary home. They spent most of their time back in Canada building a permanent home but before it was completed their tent was blown down in a severe storm and a lot of their personal effects were lost or damaged. Three children were born to them in Canada, Islay in 1906, a polio baby and two months premature, Dorothy in 1908 and Eric in 1910.

By 1911 they returned to Fiji. I recall my father once saying, “he could not get out of his head the call of the Islands with all their warmth and colour”, and having lived through three bitter winters in Toronto I have no doubt the call was strong.

On their arrival back in Levuka Dad set up a permanent studio known as Stinson’s Studio. As he was already well known as a high class portrait photographer his business thrived. He was able to settle his family in a middle class home and for pleasure built a 30’ vessel which he called the ‘Ella’. The family lived comfortably in Levuka until 1916 during which period two more children were born, Inez in 1912 and Esther (Billie) in 1914.

Island of Gau

It was in 1916 that Dad’s roving Irish spirit led him to lease from Morris Hedstrom a copra plantation on the island of Gau, 30 nautical miles from Levuka or 5-6 hours sailing time in the local copra cutters. They named the plantation ‘Dalice’. I recall my mother saying that on their arrival they found that the Fijians from the village of Garani had built them two small bures (Fijian thatched houses) in a small clearing in which they had burnt out the wild grass and reeds. They were encircled therefore by dense shrubs, trees and reeds and the first problem they really had to face was the mosquito menace. This they never really overcame until they had cleared a very large area of land and introduced lawns and gardens. They could not afford cows and my mother had to rely on condensed milk to feed her babies. I recall that they had bought and taken with them five hens and a rooster but they lost these through mosquito bites and it was two or three years later that they learnt you had to put kerosene in dripping and rub it on their combs and wattles.

In 1915 my mother returned to Levuka to give birth to my sister Olive. When the babe was a week old Captain Garfield who sailed a cutter owned by Mr Baker on the island of Narai, visited my mother and said he could take her back to Gau that day and although there was a preliminary hurricane warning out they would have plenty of time to make the island of Gau before the storm descended upon them. Captain Garfield misjudged the speed of the storm and shortly after leaving Levuka faced very high seas and found it impossible to make his way back to port. They were caught in near hurricane winds and my mother often felt the vessel would swamp and sink.

Captain Garfield who was wearing a heavy woollen sweater placed my sister Olive inside his sweater and tied a rope around his waist so that she could not fall through. He got my mother to lie down on the cabin top and tied a couple of ropes over her to give her support. After a day and night of being buffeted about they were wrecked on the reef of the island of Batiki some 18 miles from Gau.

In the days of no radio communication and very few visiting vessels my mother and sister lived in a village on Batiki for some 14 days before help came. I remember a story my mother often told of a craving she had for meat as the Fijians on the island lived mainly on seafood and she was tiring a little of it. One afternoon she was told by the Chief that they had prepared some meat for her evening meal and she looked forward to this meal with great relish. However, all her taste buds failed her when they carried in, on a tray, the complete hind portion of a dog that had been boiled and no doubt with a little salt added.

Next in line was myself, Charles Alexander. I was born on June 22nd, 1919 and this was my official birth date until 1979. It was only then when I applied for a birth certificate from the Government that I found my date of birth was supposed to have been 10th June 1919 and I can only assume a mistake was made somewhere along the line when dates were asked for on earlier occasions when my parents were seeking certificates. I know I was born on June 22nd because I certainly fit into Cancer far better than I do Gemini. Most of my friends also agree that I could never be a Gemini.

Another interesting point was that I was always called Charlie in the family, later nicknamed Chas, but my birth certificate shows that I was christened Charles, a name that I had always used myself when filling in forms.

As I left the island of Gau at the age of four, I do not remember much about it other than that I spent a great deal of time on the sandy beach in front of the property splashing in the warm tropical waters. One or two incidents do still remain in my memory. One was a coconut log bridge across the creek at the village of Garani some ¾ of a mile from our home. I always considered it a great feat to cross the bridge unaided.

My father got on very well with the Fijian people and I recall one occasion when an argument developed between my father and the Buli (chief) Garini. Dad was crossing the bridge into the village to speak to him again on land matters when the argument started. The Chief had an axe with him and threatened to hit my father if he dared step off the bridge onto the Garani soil. My father decided to proceed and much to his relief the Chief took no further action with his axe.

Three miles from Dalice were our only European neighbours. A family called the Fryes. They had come out from England and were rather well off. They had a lovely plantation home with a flagpole in the front garden from which they flew the Union Jack flag. It was always a treat for us to walk the three miles with our parents to visit the Fryes on Sundays. The scene from a divide one had to cross along the way and about a mile from the Fryes property still lingers in my memory to this day. It was rather breathtaking.

Another vivid memory was of my brother Eric being stung by hornets. My father had taken a shot at two flying wild duck. He managed to get one and it fell into the tiri (mangrove swamp) so Eric ran in to retrieve the bird. On the way he ran into a hornets nest some 9-10” in diameter and hit it chest high breaking the next from the branch it was built on. The hornets swarmed around Eric and he received bites all over his body, up his short trousers and down through the neck of his shirt. Within hours Eric had swollen badly and to a point where he could no longer open his eyes nor mouth and for a couple of days he had to be fed through a section of paragrass which, when cut, was not unlike a small drinking straw. Eric survived.

My sister Billie had the job of milking the family cows (2). On one occasion she did not tether the cows but merely called them and they would come and stand while she milked them, but a calf kicked over the bucket of milk. My father who had gone out to see what progress had been made was most upset and was in fact so angry with the calf he decided to give it a worthwhile kick in the rump. In his temper he put full force into the kick but fortunately for the calf and unfortunately for my father his big toe contacted a stump before it reached the calf, resulting in a doubled up father nursing a broken toe. I have no recollection of Dad trying to kick a calf again.

Return To Levuka

My brother Roland was the next in line and he was born one year before our family left Gau and the last member of the family, my sister Joy was born the ear after we returned to Levuka. My father had to give up the island plantation during the depression years and shortly after the war when coconut oil demand fell rapidly with the decline in munitions manufacturing. He possibly would have struggled on but he was let down badly by Mr H. E. Snell who was then managing the company of Morris Hedstrom Limited from whom my father had leased the plantation.

This came about when on one of my father’s visit to Levuka he met an Englishman named Tom Howley who was unemployed and desperately in need of help. Dad offered him work at Dalice but said that apart from tobacco and an extremely small wage all he could offer was a room and lodging in return for some assistance with the plantation. Howley accepted the position and joined our Swiss Family Robinson who had by this time built a two storey box-like home.

On one of Mr Howley’s visits back to Levuka he approached Mr Snell and said that there was no likelihood of my father meeting his debts and promised Mr Snell that if the lease could be made over to him he would see that every penny was paid up. Mr Snell arranged for the transfer of the lease and when Mr Howley returned to Gau he told my father he was now the owner and asked if the family could move within some 2-3 months. In 1923 the family returned to Levuka. Referring to Mr Snell, my father later rebuilt his fortune during World War 2 and built a beautiful mansion in Tamavua right next to Mr Snell who needed to borrow money from my father to avoid financial ruin. How the tables in life can turn and my father’s obviously Christian spirit could forgive and help a man who years earlier had ruined him.

Move from Levuka to Suva

Levuka in 1923 was still very much a wide awake town even though Suva was taking over as the capital of Fiji. We first lived in a home beside the main park and close to the Royal Hotel. This home had several concrete paths cris-crossing each other in the side garden and in the corner of the property was a large frangipani tree. Between the cris crossing paths my mother grew flowers and as children we had a great deal of fun playing tag in and around the flower gardens.

My father was given employment by Morris Hedstrom Limited and was in charge of their packing room. I used to spend idle moments sitting on packing cases watching my father supervise the labour. I was sent to the Levuka Public School in 1925 and have fond memories of my years at the school. I also remember the swimming hole which was known as the Falls, just above the school and here we spent many happy days picnicking and swimming.

My closest friend was Drika Powell who lived two doors away from us. Their house was built on stilts and we youngsters were able to walk under the house without stooping. Motor cars were fairly new in those days and so we used to build endless roads in the dust under the house and push around little blocks of wood which we called our cars.

On Sundays we were taken by our parents to the Holy Redeemer Church and some of us used to help pump the organ. I needed assistance as the pump was fairly heavy for a youngster.

My father’s income was small so we had to find our own money if we wished to go and see the old silent, black and white movies on Saturday afternoons. We were able to collect and sell bottles and it was not too difficult to raise six pence a week to cover the cost of the movies.

I shall never forget 1928 when Kingsford-Smith landed the Southern Cross at Suva. We were told at school that the aircraft would fly over Levuka on its way to Suva. Mrs Bailey, our teacher, took us all up to a high point above her home where we sat for two hours waiting for a glimpse of the Southern Cross. There was great excitement as no one had ever seen an aeroplane. Just at the end of the second hour when we were about to give up hope of seeing the plane we heard its motors and sure enough it flew over Levuka at a height of about 1500’.

For the next two or three months our thoughts shifted from motor cars to aeroplanes and my school mates and I could often be seen with arms outstretched buzzing up the playground. At the end of the year my mother dressed me up to look like Kingsford-Smith. I had a white overall type of suit with a white helmet pulled down over the ears and a cheap pair of Fijian diving goggles on my forehead. By outstretching my arms I formed the wings of an aircraft as the material was designed to hand down some 6-8” from the sleeves. On the wings my mother had pained the aircraft’s identification. I was very proud of my costume and in fact won a prise but I complained bitterly throughout the evening that my arms were hurting me as I was growing tired holding them out. I was told to put them down to rest but this I was not prepared to do as I would no longer look like an aircraft.

The last 18 months in Levuka we lived in another home located on what is known as Mission Hill and to reach the little street serving the three houses on Mission Hill one had to climb a flight of some 200 steps. The land behind the Mission was used by various Fijian families for growing cassava (tapioca). Young tap roots when only 6-7” long are rather tender and the juice sweet, so we used to creep into these patches and root up the occasional plant to find the young roots. At times the Fijian owners would spot us and give chase but we were able to move very quickly and unseen through the patches as the plants were higher than we children and the Fijians would not run in a direct line to avoid breaking the plants. We never did get caught.

The only other memory I have of Levuka was of marrying my brother Roland to Shirley Maine. Five or six of us had gathered together and persuaded Roland and Shirley that they should get married and that we should marry them in the Methodist Church at the foot of the 200 steps. We eventually climbed in through one of the side windows and the wedding ceremony was performed with dignity. Shirley holding a bouquet of flowers with a scarf as a veil and Roland in his khaki shorts and white shirt and tie looking very much the part. I cannot recall the words used for the wedding ceremony but everyone thought the ceremony impressive.

After leaving Levuka I never revisited the town until I was about 17 years of age. I went back with memories of long shaded streets, of an enormous public park and great buildings and was surprised to find that none existed and that everything was in miniature size.

In 1930 my parents decided that we should move to Suva. To us this was as good as going to another country as we had never visited another town of any size and we had heard a great deal about Suva being much larger than Levuka. We boarded a ship called the ‘Adi Keva’ and our friends were on the dockside to wave us goodbye. We travelled around Ovalau Island into Bau waters and then entered the mouth of the Wainibokasi River, a branch of the Rewa River which winds through the delta lands passing many villages on the way.

Some of the bends were so sharp that crew members would wait poised on the bow and before reaching the bend would dive overboard, quickly climb the bank and place a hawser over piles provided to help turn the vessels. The hawsers would be made fast on deck and the bow of the ship would pivot around the pile. This was great to watch and no doubt the captain and crew were extremely skilled for there was no mishap.

From the Wainibokasi we travelled down a portion of the Rewa River then through a small branch river that led us into Laucala Bay. From this bay we got our first glimpse of the Suva Peninsula and were highly disappointed as there was hardly a building to be seen. Little did we realise that the town proper was on the other side of the peninsula facing Suva Harbour. As we rounded Suva Point the town started to reveal itself and we stood there, open mouthed, looking at the great wonders of Suva. It was certainly enormous when compared to Levuka.

Schooling Suva Grammar

On arrival in Suva I was kitted out for my new school – The Boys’ Grammar School. The building was rather impressive and was situated half way between the Grand Pacific Hotel and Suva’s centre. The school was built on stilts some 7’ above the ground, was two storied and had two towers. Upstairs was used for boarders and downstairs was classrooms. It was built on reclaimed land and on one side was the Suva Bowling Club, on the harbour side was the sea wall with tidal flats and these flats extended down the southern wall back to Victoria Parade. The school at high tide had 3-4’ of water along its southern and western walls.

I was very proud of my school uniform – a cap much like the English school caps and the badge was a lion rampant and the motto was ‘Du Et Mon Droit’. We wore a white shirt, khaki shorts, and long stockings with two yellow bands – a great change from the Levuka days where there was no set uniform. However the wearing of this uniform did not turn me into a scholar.

I started off on the wrong foot with my first teacher, Miss Atherton, and spent two years in her class. She used me as an example of a no-hoper to the extent that she gave me an inferiority complex that I found very hard to overcome in later life. Strangely enough some 25 years later when I met Miss Atherton in Western Australia (she was a friend of my brother Roland) we became quite close friends and each time I go to Perth I visit her.

Probably one of the reasons I was so often in trouble was because I was full of pranks and led several other boys to assist me. A few examples – we would catch a small Dadakulace (black and white stripped sea snake) and put it into one of our pockets, then we would muddy our hands and move up to a new boy and ask him politely if he would be kind enough to get the handkerchief out of our pocket. Naturally the boy would reach in and find himself holding a wriggling snake. Many panicked, some wept and reported on us but the custom never died and went on through our school days.

We always worked in little gangs of four or five and in my gang I had Alan Kirkham, Charlie Martin, John Wisdom, Jack Gosling and every now and then one or two others. We used the soapstone fill under the school to build forts and an old corned beef barrel with its end knocked out made an entrance large enough for us to crawl through to enter our forts. We used to hold battles dodging from post to post until eventually we caught an enemy. He would be dragged back into our fort and his hands and legs would be tied. We would leave him there for an hour or two depending on what time of day it was but so that he would miss a class, then he would be released. Few reported us but many did not for fear of being caught again. The old fort system was taught to us by the older boys and we in turn taught the younger ones and it went on for many years and a lot of fun was had by all.

On another occasion my teacher was a Mr Thompson who always dressed in the most spotless white starched longs and shirt and tie. He was fastidious about his appearance and was quite ruthless in using the cane which tempted us to trick him. A dog had died under the school and the fleas lived on the dead dog and multiplied in great numbers and if we went under the school to the spot where they were, in no time they would be crawling all over your legs. One lunch hour four or five of us would spend in relays in the patch, getting our legs coated in fleas and rush up and brush them off under the teacher’s desk.

When the afternoon lessons started it was not long before Mr Thompson was leaning down scratching his ankles. The scratching became more vigorous and higher until he eventually excused himself, gave us some reading to carry on with and disappeared to his quarters upstairs. 15-20 minutes later he was back and freshly dressed and when again the fleas were crawling on him he suspected something had happened and demanded to know who was responsible. Clarrie Bradman, a pimp of the first order, who always curried favour, stood up and said it was me. I received six lashes and many 100’s of lines of writing.

Some 3-4 months later, having forgotten the hiding, my gang caught a Qitawa in one of the low tide pools. This is a scavenger fish with black longitudinal stripes and about 8” in length. We discussed what we should do with the fish and finally decided to nail it to the bottom of Mr Thompson’s desk immediately behind the drawer where it could not be easily seen. Things were okay for the first day but by the second there was a slight fishy smell and by the third things were getting pretty bad. It was not until the afternoon of the fourth day when many of the youngsters in the first row asked to move back because of the bad smell that the fish was discovered. Fortunately no one in my gang reported me and Bradman did not see me put it there but I can remember Thompson questioning the class with his eyes always coming back to me. I am sure he knew I had done it but could not get proof.

We had a new boy from England who was a bit of a sucker. He sucked in anything you told him. For several days we talked of the annual cross country race that was to take place on the last Saturday of that month. We told how we would swim the harbour from the school to Lami, climb Mt. Korobaba (1200’) then race back around the Lami Road to the school. He said he could not swim properly but we said that would not excuse him as the boats that followed would pick up those that could not continue but they would still have to carry on with the mountain climbing and the run back.

We told him that because of the slippery clay on the mountain he would have to have a pair of shoes with spikes and as he did not have a pair we suggested that he should bring down his best pair of sandshoes. This he agreed to do and in the meanwhile we collected about 24 clouts, 1” in length, took his shoes and put 12 clouts through each shoe and gave them back to him the next day. Strangely enough he thanked us very much indeed for helping him. I do not know what he thought when the last Saturday of the month came and passed and there was no race.

Another point that comes back to mind was our sailing rip in John Wisdom’s 10’ sailing dinghy up the Lami River to pinch oranges from a large orange grove in the area. The usual gang was with me. We ended up with 40-50 oranges, came down the river and started to sail across Suva Harbour. Our first tack took us to the main Suva Harbour reef passage. As the wind was blowing from the west our sail hid the view of the bay from us and we did not realise that the ship ‘Waihimo’ was making down on us as we neared the centre of the passage. It was only when she started hooting that Alan Kirkham looked under the sail and said there was a big ship coming straight for us. I immediately jibed and tried to clear the passage. As the ship passed very close to us her bow wave turned us over and left us clinging to an upturned sailing dinghy with oranges floating in all directions the ship carried on through the passage to the open ocean and we started to drift in the same direction with the outgoing tide.

When the five of us clambered onto the bottom of the dinghy it would sink and so we swam around until it resurfaced and tied again. We repeated this process over and over. While floundering in the water we would try and collect the oranges again. We thought we had been abandoned. As I as a regular church-goer my friends asked me to say a prayer for our survival so we all clustered together and said the Lord’s Prayer.

We then saw the Waihimo turn when it had sufficient room and saw a lifeboat half way down her side and it was returning for us. We did not know that they had radioed the Harbour Master to send out a launch. The lifeboat reached us first and took us back to their ship which was now back in Suva Harbour. We were cold and furious. When the pilot boat came alongside we were transferred and knowing we were back on Fiji property our pride returned and several of us raised our fists and shook them at the captain of the Waihimo who we thought was in the wrong.

On Saturdays we would often go out shooting doves using Daisy airguns. If we were lucky enough to get two or three doves we would then dress them, set up a fire, and with ingredients from home make what we called pigeon curry. At one stage John Wisdom’s father gave him a high powered slug airgun and one Saturday in the paddock next door to Garnett’s home near Pender Street, two rival gangs had a war. Each gang sought protection from the high grass and scrub and whenever John sighted an enemy he would take a pot shot at him with the airgun. The Daisy airguns would give you no more than a sting if hit by a pellet, however if hit in the eye it could be extremely dangerous.

The slug gun was a different matter. John hit one of the Kirkham boys in the rump and the slug embedded itself about ½” under the skin. Very quickly after this he fired another slug and got Charlie Martin (I think) and again embedded itself in his cheek below the eye. The agonising cries from these two victims soon brought the war to a close. We were all given hidings and told the guns would be taken away if it ever happened again.

Guy Fawkes night was far from safe for the innocent two or three who made up a little Guy and carried it around the neighbourhood, singing the usual song and holding out a hat. Larger gangs would form and they specialised in catching the small teams and robbing them of their takings.

On one occasion my brother and I fooled the gangs by dressing up Keith Chandley who was a minute fellow, as a Guy. We propped him up in a kerosene case which we carried by fastening two long handles down each side. We were attacked by a gang near the Colonial War Memorial Hospital so we took off with a tin of money, the tin was slotted to receive coins and in it we had three or four pennies. They caught up with us and took the tin away from us and cursed us for not having collected more. While the gang chased us, Keith Chandley, with our proper collection tin, darted off in the opposite direction and managed to reach home safely with our takings.

1932 – 33 Pidgeon Fad

Alan Kirkham started it off. Alan was always fond of keeping white leghorn chickens and was a very successful keeper. One day he decided to catch some of the town’s pidgeons which he caged and tamed to stay around his property. His action started a craze and for memory John Wisdom, Jack Gosling, Ken Perks, Charlie Martin, Ah Sam and myself all built pidgeon coops and started to collect pidgeons. Ron Kermode also took an interest in pidgeons but he had an automatic loft in the ceiling of the shed at the back of his father’s home. His father’s home was in the centre of the Suva Police Station as his father was the Senior Officer of the force at the time.

We caught our pidgeons by building small traps some 4’ long, 1’ high and 3’ wide. We covered the sides and the top with wire netting leaving the bottom open. We would then get a small prop and prop the cage up at one end and attach a long string to the prop to trigger it. We would then throw wheat or corn or bread scraps under and about the cage and wait for the town pidgeons to descend. I used to set my trap up on the main street of Suva, Victoria Parade, some 6’ out from the curb and directly in front of the fire station – the traffic in those days was not very plentiful and the drivers obligingly drove around the trap. However it was not many days before I was told I must catch them somewhere else. We then started using the vacant lot on which the Regal Theatre now stands.

One of our friends told us the best way to catch pidgeons was to get them drunk and to do this you had to soak wheat for about a week in neat whisky and then feed it to the birds. In no time the birds would become intoxicated and flap around senselessly. It was at this stage we would rush in and grab hold of it. The great problem was finding the whisky as most of our parents did not drink, or if they did, only a little wine or an occasional beer. However John Wisdom’s father was a keen whisky drinker and we had to rely on John for our whisky supplies. This lasted for two or three weeks and no doubt his father discovered the shortage and locked up his stock.

After we had become well established with some 20-30 pidgeons each we started to admire one another’s birds and the only way to get hold of these was to pinch them when your friends were not watching. The best time was when they were not home and we would ask the parents if we could see the birds. This did not get us far as everyone was up to the same trick.

The great haunt for this was the pidgeon loft in the centre of the Police Station, Ron Kermode’s birds as he called them. We used to go down with empty school bags when we knew Ron was playing cricket or football and ask Mrs Kermode if we could climb into the loft to see the pidgeons, always saying Ron said we could. In no time we would catch five or six birds stacking them in our empty school bags head to tail, much like sardines in a tin. We would then have the audacity to return to Mrs Kermode to thank her, hoping that one of the pidgeons would coo.

The Ah Sam’s ended up getting some Squab birds and these were highly prized so one day we planned to have a night raid. Alan Kirkham, John Wisdom, Jack Gosling and myself. We must have been spotted on our way up because we managed to get to the pidgeon coop and were just about to enter it when a flashlight went on and a lot of Chinese voices started calling out. We tore down the hill and made for the bush at the bottom of the garden. I jumped sideways into a bamboo clump and there I stopped. The other three were caught and Mr Ah Sam told them he was reporting the incident to their fathers. My great friends started calling from the road, “Come on out Charlie they know you are with us, we have told them”, but I decided not to move. About half an hour later I crept out and went home. The result being my father was never told as there was no proof of my being there and the other three boys get a hiding of their lives.

There was only one other planned raid. I was invited to take part but refused as I had had enough after the Ah Sam case. This was to raid John Wisdom’s pen. What had happened was that when Alan Kirkham was in Auckland John raided his pen and took some 20 birds. John then went down to Auckland to school and met Alan who was returning to Fiji and no doubt, feeling guilty, told Alan that he had borrowed 20 of his pidgeons for mating and that when he got back to Suva he could go up and get them. John said he would write to his father about it. When Alan called on Mr Wisdom he was told that John had not written any letter and none of the pidgeons could be taken so Alan decided that they would raid this pidgeon coop. A gang of six was formed including Frank Gosling and Onslow Kirkham who were both about 17 or 18 and could have got into trouble if caught as they would be dealt with as adults.

On their way to the Wisdom’s property the Wisdom’s cook boy spotted them and guessed what their mission was. He followed them and then quickly went in and told Mr Wisdom but the cook had allowed too much time to pass by following at a distance and the boys were able to get some 20 pidgeons or so and disappear. The next morning I went to see how they had got on and found the group sitting around Alan’s pidgeon pen talking of their success. While I was there the Black Maria arrived followed by a car, out of which stepped Inspector Hooper. He walked down to the boys with two constables and said, “Right oh my young fellows, we know all about it and I want you all in the Black Maria”.

The younger boys swore that Frank and Onslow were not with them and I told Inspector Hooper I had nothing to do with it. He said he did not believe me but fortunately the others said I was not with them and I was allowed to go home. All were lined up in front of Mr Kermode who was Commissioner of Police who gave them a thorough dressing down and told them if it happened again or if he heard of any more pidgeon pinching, those caught would get the birch. He said they were all free to catch the town pidgeons in a fair way as long as they were not for killing and eating and this is how it all ended. The pidgeon pinching stopped and for mating purposes we learnt to borrow and lend each other birds.

Another occasion was my going home in a thunderstorm. I was walking up a one way street beside the Methodist Centenary Church. I knew the storm was close and I was petrified because the thunder came at almost the same time as the flash of lightening. All of a sudden a ball of fire, that is the only way I can describe it, about 6’ in diameter, hit the road some 40’ ahead of me at the same time as a clap of thunder. The ball of fire was brilliant and frightening and I really thought I had seen my last day.

At the beginning of this school section I said Miss Atherton put me off school. She really did and I hated it and many mornings, to avoid going to school, I would climb up the mango tree and my mother would be left below pleading with me to come down. Sometimes she would get one of my older brothers out with a bamboo stick to try and poke me out of the tree and of course I always did as I was afraid of the stick and was off to school with my lunch in my bag, weeping my eyes out. Of course this was only in the early days of school but once I left Miss Atherton’s class I certainly did improve and after Mr Thompson’s class I got into the Headmaster’s class, a Mr de Montauk.

I upset Mr de Montauk on one occasion. I cannot recall now what it was, but he had the habit of saying, “if anyone knows anything about any pupil in this school it is Miss Atherton, how you come along with me young Stinson”, and he took me out onto the veranda and told me to wait and went and got Miss Atherton from her class. He brought her over and said what do you know about this young man? Miss Atherton went to town and said I was undisciplined, no ability to learn and a whole tirade of abuse. Mr de Montauk thanked her and she went back to her class. He put his arm on my shoulder and said she was not very kind was she and I want you to know I do not believe everything she said. Now come back into class and be a good boy. De Montauk became my hero.

![]()